Loading component...

At a glance

- Board duties provide great scope for professional growth, an expanded network and opportunities for giving back to the community.

- Financial skills alone will not suffice; board members are responsible for an organisation's long-term future, and need a mix of technical and soft skills.

- The required skills include risk management, corporate governance, active listening and a collaborative mindset.

- CPAs wishing to gain board experience can start by volunteering on not-for-profit boards and attending professional events.

Taking up a position on a board of directors represents a huge opportunity for professional growth. Board duties carry with them the promise of an expanded network, an intellectual challenge and the chance to give back to the community. A directorship also enhances a CV and raises a person’s public profile, which may lead to further career opportunities.

Li Li Kuan FCPA encourages senior practitioners to seek out board roles, as having finance expertise is particularly valuable in today’s increasingly volatile and uncertain business climate. As an independent director on the board of CapitaLand Retail China Trust (CRCT) in Singapore, she says it helps her evaluate the pros and cons of funding and implementing different strategies.

Landing that first board role

However, as a board member is ultimately tasked with securing an organisation’s long-term future, financial skills alone will not pass muster. Practitioners need to develop additional skills, of both the soft and hard variety.

“There is a particular mystique around getting that first board role,” says David Jenkins, CPA Australia’s former New South Wales general manager.

“It’s a mistake to think that things will just fall into place towards the end of your career. There is a process involved, and you need to think about how you’re going to achieve it.”

To that end, in late 2019, Jenkins organised a CPA Australia members event in Sydney that provided practical tips and insights on making the transition from management to board member.

“A lot of our members understand the nuts and bolts of finance to an extremely high level, but getting on a board requires developing other skills,” he says.

Karina Kwan FCPA used her address at the event to outline the types of qualities that board member contenders must possess.

“As an ex-CFO, just bringing financial expertise to a board isn’t going to be enough. You need to bring other skills, such as risk management or corporate governance. In addition are soft skills such as active and respectful listening, the art of asking insightful questions, and having a collaborative mindset,” she says.

Kwan gained her first board experience in 2010 at Learning Links, a non-profit organisation that supports children with learning disabilities. At the time, she was the corporate treasurer at Citigroup in Australia and New Zealand.

“As I was working at a bank, I had to seek permission to become a director at another organisation. It was fine because it was in a non-compete sector and it was pro-bono.”

She took on her first full-time, non-executive director role eight years later at WAM Active Limited, which is ASX-listed and part of the Wilson Asset Management group.

As soon as she knew that she would be transitioning to full-time directorship, she completed the Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) course. She says it was invaluable, and that by the end, graduates will know whether a directorship is right for them.

“[The course] covers the duties and responsibilities of being a director – and some of those are scary. You learn about what directors can be liable for. Ultimately, your duty is to the company as a whole, which means the shareholders, or in the case of a superannuation fund, the members.

"As the case law has developed, this has gone from just shareholders to a much wider set, termed stakeholders – that is the employees, shareholders, members, and the community at large.”

Kwan says it is imperative to do your homework to avoid getting in hot water.

“Be careful about getting on the board of a company if you don’t quite know how they make their money or what the regulatory environment and customer environment are like. It’s important to have some familiarity with the industry, too.”

Board member benefits

Many are drawn to non-executive roles for the flexibility they offer. Kwan, for example, is able to divide her time between her board duties, advising fintech start-ups and lecturing at the University of Sydney Business School, where she is an adjunct professor within the discipline of finance.

As the father of two young children, flexible working arrangements also appealed to David Maywald. After more than a decade in the fast-paced world of funds management at RARE Infrastructure in Sydney, when the company was taken over, he seized the opportunity to create a better work–life balance.

“Proceeds from the takeover gave me some flexibility to reduce my hours. I felt that I’d accomplished everything I wanted to in the role, and that there were other things I wanted to contribute to the community.”

To find out whether a directorship would be a good fit, Maywald got active on the subcommittee of his cycling club.

“I realised there are a lot of areas where I had skills and experience that could be used for the greater good. I’ve been a keen cyclist most of my life, and cycling is something I wanted to contribute to at a higher level,” he says.

When an opportunity arose to join the Bicycle NSW board in 2018, Maywald leapt at it.

He has since joined a second board – SolarShare Canberra – and says that while board membership certainly looks great on a CV, it shouldn’t be the sole reason for pursuing a directorship.

“It takes up time, and you’re probably not going to get paid for it. I wouldn’t do it just to get the next leg-up. You need that intrinsic motivation of doing something for the community.”

Finding time to do it all

Although Maywald was already working part-time when he took on his first board role, he says that the workload would have been manageable with a full time job.

“A lot of people don’t realise that you can hold down one or two board positions when you’re in a full-time role. Meetings are usually held monthly, and tend to be during the evening, so it doesn’t clash with your full-time responsibilities. Also, the work in between meetings tends to be quite flexible,” he says.

However, Maywald added that the first few months of his directorship were intense, with a long reading list and time spent building relationships. Both are necessary to successfully switch from a manager mindset to that of a director.

“The issues you’re dealing with tend to be big picture, complex and interrelated.

“It’s expanded my thinking as I came from a quantitative area like finance, where numbers are so important,” Maywald says.

"There is a lot of competition for board roles. While recruiters play a role, the most successful way to obtain a board role is through your network."

As executive director of Women on Boards (WOB), Claire Braund acknowledges that women are more likely to have carer roles plus professional duties, and may therefore feel especially strapped for time. She nonetheless urges women to seek out directorships, saying those accustomed to balancing competing demands make excellent board members: “It’s the busy women who are on boards, having children, and getting things done. That’s just the way it always has been, I think.”

If it’s only possible to take on one board position, she says it is important to choose carefully and be strategic. Non-profit or government boards may be less demanding time-wise.

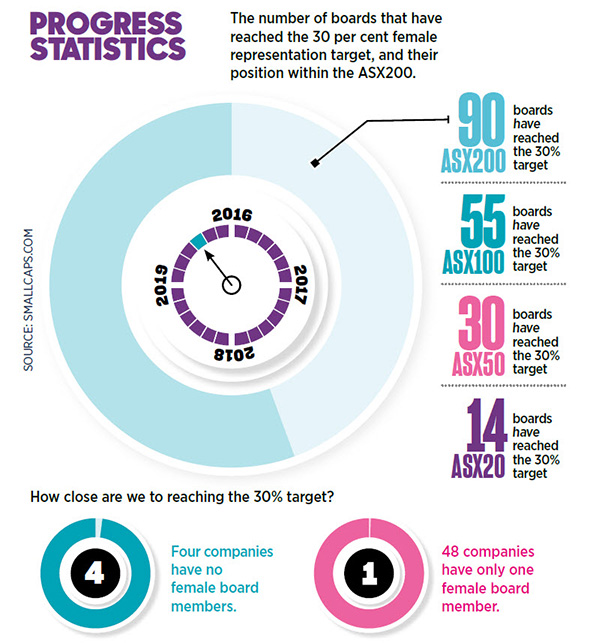

Braund cofounded WOB in 2006 with the aim of increasing the numbers of women in non executive roles. While progress has been made, more work remains. The latest Gender Diversity Report released by AICD reveals that as of June 2019, women represented 29.7 per cent of directors on ASX200 boards. This falls short of meeting the target of 30 per cent by the end of 2018.

“Recruitment is a very variable process. People still recruit from the pool of people they know,” Braund says, adding that WOB has set a higher target of 40 per cent female representation.

WOB uses an algorithm to match its members with board vacancies, which can also be accessed free of charge on its website.

“We flipped the model to make [board] vacancies transparent, because the more transparency you get, the higher the likelihood of women applying,” Braund says.

Network, network, network

Kuan had three decades of corporate experience in Asia-Pacific when she joined the CRCT board in January 2018.

She says that those who wish to gain board experience should raise their visibility by volunteering on a non-profit board and attending as many events as possible.

“There is no clear-cut path for candidates to position themselves for board selection. Besides building a strong network and having the necessary skill sets and knowledge, you should also bring energy, enthusiasm, commitment and ideas,” Kuan says.

Kwan agrees that networking is vital. For better or worse, it is a matter of who you know.

“There is a lot of competition for board roles. While recruiters play a role, the most successful way to obtain a board role is through your network. The people you know can refer you as someone who might be a good fit,” she says.

While some dread formal networking, Maywald discovered he relished it.

“I contacted people I’ve met over the last 20 years and went back to friends from university. That’s been fun. Getting a coffee doesn’t take much effort and most people are really welcoming if you are genuine and they can see that you want to make a difference.”