Loading component...

At a glance

By Stephen Corby

It can bleed you of hundreds of millions of dollars and may end up costing you customers, plus hard-earned loyalty and brand recognition, so why do so many big companies invest so much in rebranding exercises?

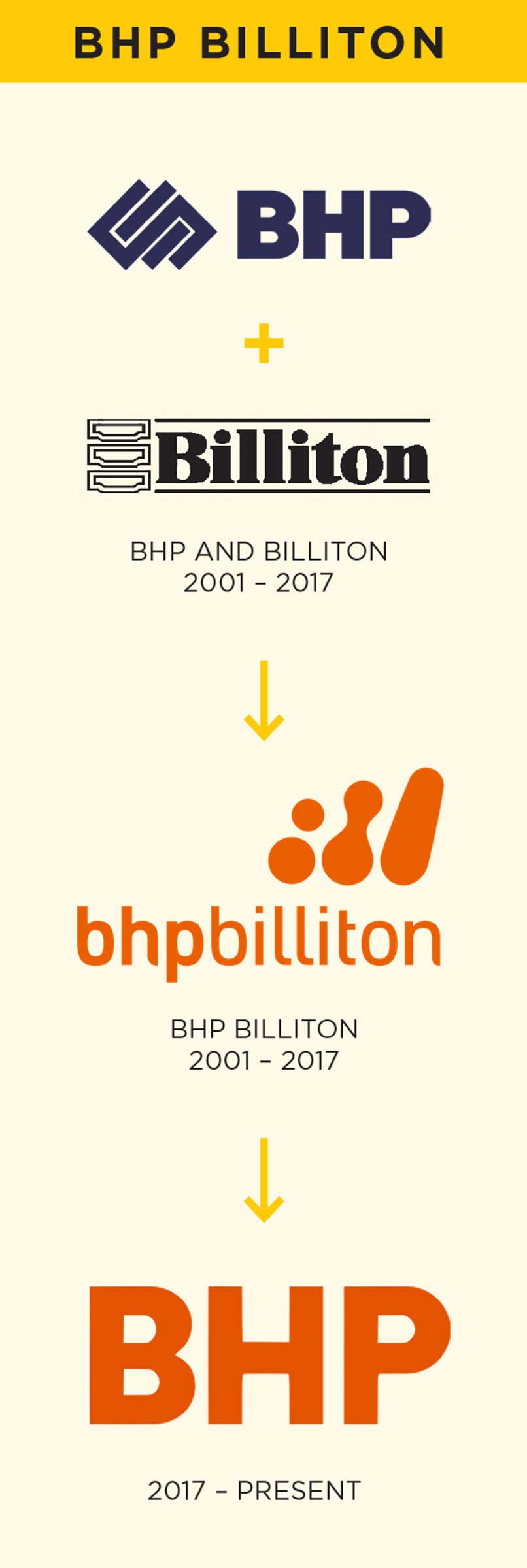

The most recent effort is BHP’s move to drop the Billiton from its name (after 16 years) and the four blobs from its logo (what were they anyway?).

Chris Baumann and Hume Winzar, associate professors of business at Macquarie University, are baffled by the move. Their research shows that rebranding rarely leads to increased profits, so are these expensive and extensive campaigns by highly visible companies about garnering attention, or do they reflect an attempt to reinvent tarnished brands?

“The two of us literally spent several hours at a desk, debating why they’re doing it, as well as [why they are] launching their Think Big tagline, because what does that mean?” a mystified Winzar asks of the change at BHP.

“Those words could apply to Qantas, or a bank, or a hamburger chain. The idea of a brand is to create emotional bonds and establish trust, but Think Big is so generic.

“The large-scale research in this area suggests that you’re more likely to lose out by rebranding, so companies don’t do it unless they’ve already lost, or they’re afraid they’re going to lose something.

“It could be BHP just happened to have A$200 million or A$300 million on hand and didn’t know what to do with it, so they spent it on a rebrand. Or it could be that they haven’t had a very good time recently, with some bad investments in things like fracking, and the Samarco mine disaster [in Brazil] … that kind of thing.”

Baumann points out that if you have a good, established brand that everyone regards as trustworthy, there is no value in changing it at all. It’s the very definition of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”.

“What you’re saying with a rebranding is ‘Here is the same product, in a new package’,” Baumann says.

“I don’t understand why people do it with packaged goods, and there’s even less reason a company would do it.”

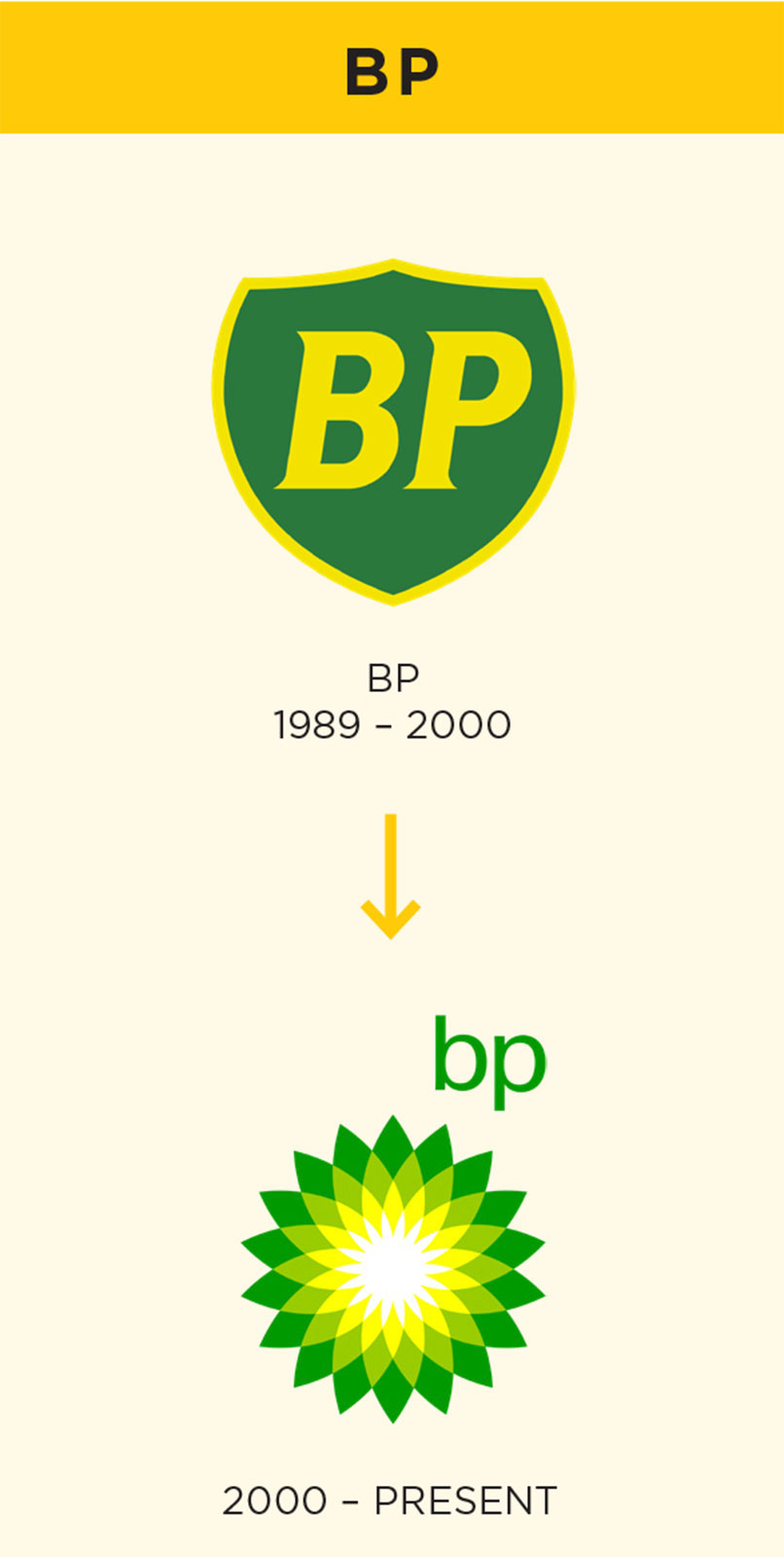

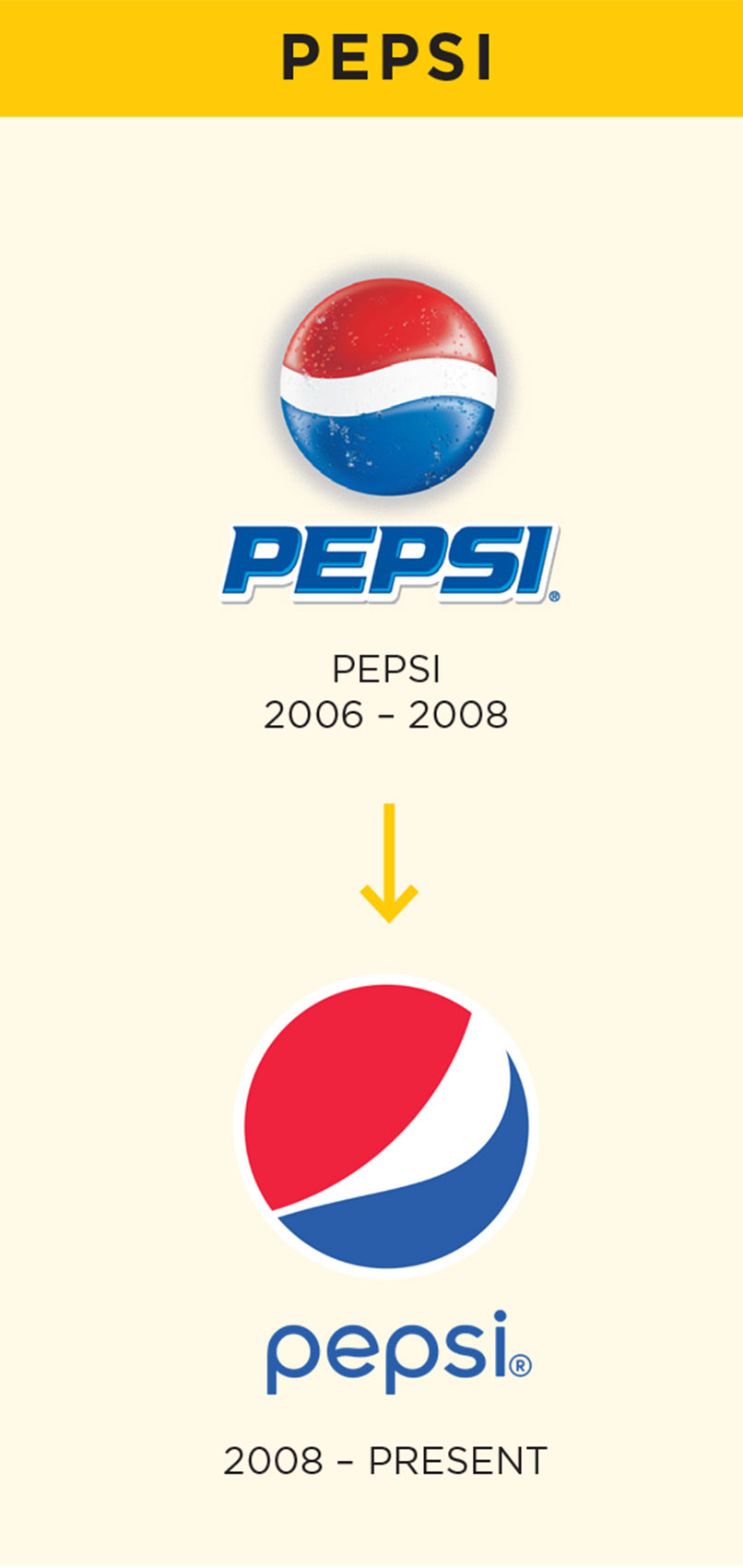

Yet companies do. BP changed its logo to its Helios flower back in 2000 at a cost of US$211 million (US$4.6 million of which was for the actual logo). Pepsi tweaked its logo in 2008, by changing the white wave across its centre into a cheeky smile; the rebrand was rumoured to have cost more than US$1.2 billion over three years, with US$1 million for the logo.

The sky-high price is because the companies are paying for everything from the consultants and market researchers, who test whether the rebrand is a good idea, to the actual implementation, which includes everything from signage on buildings down to company letterheads, websites and name tags.

Baumann says the reasons the money gets spent on a rebrand, despite the risks, are many and varied.

“HSBC really started the whole thing, on a global scale, when it went from Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation to the abbreviated form in 1991. Then everyone did it – ANZ, UBS, NAB – partly because it was a trend, but also because those acronyms sound less like a bank.

“Following the trend is one reason [for rebranding], but it can also be about repositioning, revitalising, or starting afresh. Or it could be about trying to cover something up.

“What BHP is doing is trying to completely change the brand and the brand image, and people’s understanding of and faith in the brand. Effectively what they’re trying to do is close the door and say, ‘This is a new business; we’re selling exactly the same thing, but we’re a new business. Look, it’s a new sign on the door! A new team.’ That’s the perception they’re trying to create.”

The BHP rebrand story: reconnecting with history

As you might expect, BHP’s chief external affairs officer, Geoff Healy, has a different story. He says it’s all about bringing back the magic of Bill Hunter’s voice intoning those advertisements for The Big Australian more than 30 years ago – ads that still resonate with older generations.

“This is the first time since then that we have come out with a significant campaign. Healy says.

“We decided to have a really hard look at the way people looked at us, what they knew about us, how they felt about us. We did a survey across Australia to see what people thought.”

He admits that the results were “a bit of a shock”. Very few people knew what the company did, although they knew the company name. According to Healy, people said they wanted to know more about BHP and what it is doing for Australia.

“Trust has been lost in companies like ours. If we’re going to reverse that, we have got to get out and change the way the community looks at us and thinks about us,” he adds.

“The concept of the campaign is Think Big. That’s nothing to do with being big, it’s all about thinking big. It’s about innovation.”

Returning the company name to those three simple letters is about reconnecting with BHP’s roots, says Healy. Back in 1979, Ian Crawford was BHP’s manager corporate publicity; he came up with both The Big Australian slogan and the TV campaign that supported it.

“We were the first sponsor of a then-untried program called 60 Minutes and our deal with the Nine Network gave us the opening-and-closing billboards (‘60 Minutes; brought to you by BHP, The Big Australian’),” he recalls.

“One of the things that is remarkable about the success of the campaign is that we were on only one program, on one channel, once a week. After a shaky start ratings-wise, within a few months 60 Minutes was the country’s most-watched TV program and the rest, as they say, is history.

“As soon as I left the company and a new PR regime arrived, BHP’s corporate TV activities fell into the arms of a new agency; The Big Australian was dropped and they used the late actor Bill Hunter to front the commercials with the totally forgettable slogan, ‘Australia’s BHP’.

“From the look of the new commercials, the company is back in the hands of [another] agency. I find the new commercials and the signing off on ‘Big’ quite strange, and I don’t know what the pay-off will be.”

Corporate rebrand fails and wins

Not every rebranding works, of course, and sometimes they can lead to embarrassment, like Ernst and Young not realising that its new EY brand would come up in a Google search as the name of a gay magazine in Spain.

When Andersen Consulting changed its name to Accenture back in 2001, it cost US$100 million and was widely seen as one of the worst rebrandings in corporate history. A contraction of “accent on the future”, the name was derided as the kind of branding only a team of consultants could come up with.

“Exxon was the group that did something like that first,” says Winzar. “They literally pulled out a dictionary and tried to find a two-syllable word that didn’t mean anything – ‘let’s create a brand that doesn’t mean anything, anywhere, so it can’t be misconstrued’ – and they came up with Exxon [in 1972].”

Yet some companies have benefited from rebranding, including Virgin Blue, which needed to distance itself from being a budget airline to win over more of the corporate market. Its name was changed to Virgin Australia in 2011, some 11 years after it launched.

"Trust has been lost in companies like ours. If we’re going to reverse that, we’ve got to get out and change the way the community looks at us."

“Changing the name wasn’t enough, of course; they also introduced lounges and a proper business class,” Baumann says. “That was a rebranding that included a genuine repositioning; an actual change to the product, and that was very successful.”

Winzar points to the Commonwealth Bank’s seemingly risky move back in 2012, transforming one of the country’s oldest brands into the snappy CommBank, with a new logo and Can campaign, as another success.

“When they [decided on] CommBank and launched the whole ‘Can’ thing, they were desperate. It was post-global financial crisis and their focus groups obviously told them they were regarded as old-fashioned,” Winzar explains.

“They weren’t going to lose very much by doing it. When you’re in a position where you’re regarded as quite ordinary, you can only get better. The rebranding … returned them to being a proper player. Within two years, they were the most trusted brand in that segment.”

When a name change or brand promise goes deeper

For some companies, of course, such as William Buck accountants, a change of brand, or at least what they call their brand promise, can have positive effects that ripple through not just their client base, but the staff as well.

William Buck managing director Nick Hatzistergos is proud to say it was his decision to shift the company from its turgid tagline – Strategic Thinking, Tailored Advice, Integrated Solutions – to the more involving and emotive Changing Lives.

“A few years ago I was chatting to a journalist who told me that, in her opinion, all accounting firms were the same, that we’re all boring and beige, and just different versions of each other,” Hatzistergos recalls.

“I was shocked, because I’d never thought of the firm I’d spent a lifetime building being ‘beige’. But I started trawling the internet and I realised that she was absolutely right. Everyone was using the same words, the same promises, to describe themselves.”

The decision to change to a message about change, which finally happened in 2014, was not a simple one. It involved two years of research, debate and internal buy-in from staff.

“There was a lot of worrying. People were scared, saying ‘We can’t say that, we don’t change lives, we’re not curing cancer!’?” Hatzistergos says. “But we got a really positive response from clients; they said ‘Yep, we get that, that’s a great message.’

“What Changing Lives is meant to signify is that the reason we do this is that we want to have an impact on people, on our clients’ lives. It’s also a call to arms for our people, to say you can’t change anything unless you’re constantly changing and improving yourself.”

Hatzistergos admits the process was expensive and intense, but says it has been extremely positive, and has won his company new business. Along with his staff embracing the message, that’s what has made the investment worthwhile.

Rebranding might not work for everyone, and it’s telling that the most successful companies in the world, such as McDonald’s and Coke, rarely mess with their branding.

In some cases, however, it really can be more than just shortening your name to an acronym; it can genuinely reinvigorate a brand. Will BHP’s latest Think Big relaunch count as one of those successes? We’ll have to wait and see.