Loading component...

At a glance

- Patrick McGorry has modernised Australia’s approach to mental health through a focus on early intervention and humane, community-based treatment.

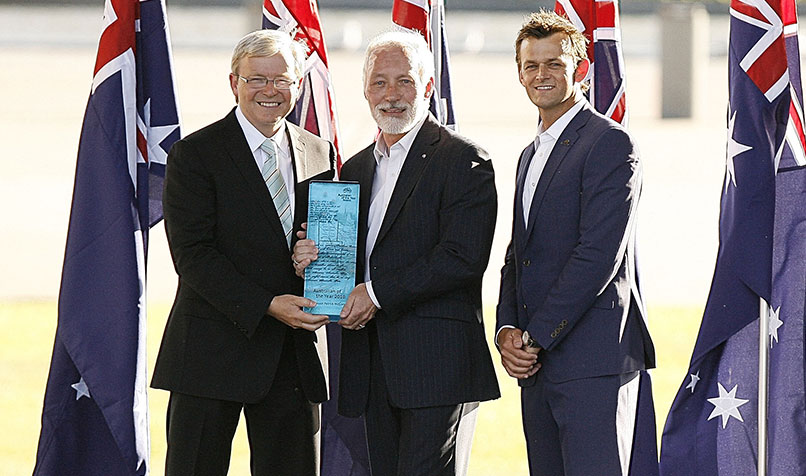

- McGorry is the recipient of numerous awards and honours, including Australian of the Year.

- He established the hugely successful headspace centres across Australia, offering mental health support for youth. The model has been replicated in a dozen countries globally.

By Johanna Leggatt

Patrick McGorry concedes he is very much a product of his era.

Australia’s most prominent psychiatrist describes himself as a reformer, a trait he attributes to the tenor of the times in which he grew up.

He was 15 when he moved with his family from the UK to Australia in 1968. It is a period often referred to as the Year of Revolutions, in which activists agitated for social change across many parts of the globe, including in the US, France, Germany and former Czechoslovakia.

The reformist sentiment gripped the young McGorry.

“I was an idealistic teenager,” says McGorry, who is now director of the Orygen Specialist Program in Victoria, Australia and a professor of youth mental health at the University of Melbourne.

“I was very influenced by those protests as a young person; I guess I was looking for a cause in my life and a way of making change.”

McGorry’s father was a doctor, and he notes “there is a lot of pressure in Irish families to choose a safe career”.

He was deeply interested in the plight of the mentally ill and considered studying psychiatry, but was initially deterred by the institutional and backward approach to treating patients.

“I just couldn’t work in those mental hospitals, so I put it off and worked as a GP [general practitioner] instead,” McGorry says.

Early intervention

Then, in the late 1970s, fate intervened. While McGorry was working as GP in the city of Newcastle in New South Wales, a newly established and forward-thinking local medical school was established, led by a leading professor of psychiatry, the late Beverley Raphael.

“She was warm and caring, and contrasted greatly to the standard approach at the time,” McGorry reflects.

“I saw then that there was a way to do psychiatry training that could lead to a humane approach, and maybe even help people who were mentally ill.”

McGorry moved to Melbourne in the mid-1980s and helped set up a clinical research unit at the Royal Melbourne Hospital – Royal Park Campus. Once again, he found himself frustrated by the antiquated approach, especially towards young people suffering psychosis and schizophrenia.

“The mindset was that they were all doomed, and yet I could see a good life was possible for those young people,” McGorry says.

"My fundamental identity is as a reformer, but people will try and undermine you or resist these changes... I understand it though, because without resistance, you're not really changing anything."

“My fellow researchers and I could see the potential for optimism and reform in the treatment of mentally ill youth.”

In 1992, McGorry set up the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC), which achieved great results based on early intervention, community-based teams and home-based care of the mentally ill.

Over the following decade, McGorry broadened the remit of the early intervention service model to focus on the full range of disorders in young people, including mood, personality and substance use disorders.

This evolved into the establishment of the research and clinical service institute Orygen, where McGorry is executive director to this day, as well as the pioneering treatment program, headspace, which offers on-the-ground help for youth in need. The program has been rolled out to more than 100 locations across Australia, as well as a dozen other countries including Ireland, the US, Canada, Denmark and Israel.

“When Steve Jobs held up the iPhone for the first time and everyone said, ‘I want one of those’ – well, it was a bit like that with headspace,” McGorry says of the centre’s success.

“When we put it into Australian communities – in a welcoming, youth-friendly way – people said, ‘We want one of those’.”

Coping with the "new normal"

Naturally, the plaudits have followed in recognition of McGorry’s work – including the titles of Australian of the Year and Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 2010 – but he feels there is more work to be done, and that this is no time to rest.

In addition to championing funding for mental health services, McGorry has set up Australians for Mental Health, a grassroots campaign body and social movement to drive improvements in Australia’s mental healthcare system.

“People can talk to their GP about their mental health, and young people can access headspace, but if a problem is more complex or enduring, and there needs to be a team-based approach or a psychiatrist involved, then that is still very hard to find,” he says.

“The Productivity Commission has estimated one million [Australians] fall into this ‘missing middle’ category, but I think it’s more likely to be two million.”

Like many health professionals, McGorry is also concerned about the long-term ramifications of COVID-19 and the flow-on mental health issues from the economic fall-out.

“The Australian Government has spent tens and tens of billions of dollars addressing the threat of the infectious disease to the economy, but so far in terms of mental health, they have just topped up the help lines and encouraged people to support each other,” McGorry says.

“That is not going to be enough, especially when the mental healthcare system was already overwhelmed with demand before COVID-19.”

Many people, too, will continue to feel the strain and stresses associated with working from home.“Working from home suits some people, but a lot of people are finding it hard,” he says.

“I read a great line the other day that said, ‘It’s not working from home, it’s living at work’, and that is true.”

Meanwhile, McGorry estimates that 30 per cent of Australians will need some kind of mental healthcare as a result of the economic ramifications of COVID-19.

“If people are out of work, they lose their sense of identity, and we know that suicide rates do go up in times of recession,” he says.

“The GFC [global financial crisis], and the tough austerity policies that followed globally, was a major driver of suicide risk and mental ill health. The temporary threats are not as significant as the long-term ones.”

The funding needs

McGorry has spent decades advocating for change, but acknowledges that it wasn’t until his Australian of the Year award that he was able to most fully leverage his leadership skills among the halls of power.

“I have spent the past decade since [the award] trying to make my case and working with friendly politicians,” he says.

hen it comes to pushing for change, “it’s important to state that it is not a party political thing, as there are sympathetic politicians on all sides.”

For business leaders advocating for change, McGorry cautions against a heavy-handed approach.

“Rather than just saying, ‘You’re not giving us enough money’, offering hope is important,” McGorry says.

“You have to offer a solution. You need to say, ‘If you want to fix this problem, here is what we can try’.”

McGorry argues that just as the broader health sector and government have been slow to support mental health, the business sector needs to step up as well.

“Mental illness is the most important non-communicable disease and has twice the economic impact of cancer,” he says.

“It affects young people and those in the prime of their life, and yet the relative investments in cancer and mental health are like chalk and cheese.”

McGorry would like companies to invest widely in mental health research as part of their corporate and social responsibility frameworks.

“It’s so easy for corporates to go to the knee-jerk, usual suspects when funding causes, such as cancer charities,” he says.

“Not that these are not deserving, but there has to be a sense of what is the best use of resources and money.”

Companies, he argues, need to go beyond an internal mental health framework for their employees and fund the external research that undergirds the programs they rely on for staff wellbeing.

“If the corporate sector wants to invest in good mental health for their workers, they have to invest in us and our research,” McGorry says.

“It’s not going to come out of thin air.”

No one is immune

While a large portion of his professional life has been spent advocating for the rights of society’s most vulnerable, McGorry is keen to point out that poor mental health does not discriminate.

“People from affluent families can suffer enormously, just the same as poor people, and it is a basic human right to access skillful and humane care.

“Anyone in a position of status may feel they have got nowhere to turn to. If you’re in a senior position with a mental health issue, it can be very dangerous, as you feel that you can’t reach out.”

At times, fighting for better mental healthcare has taken a toll on McGorry, who has faced resistance from some quarters opposed to change.

“My fundamental identity is as a reformer, but people will try and undermine you or resist those changes, and the tactics used are sometimes not very nice. I understand it though, because without resistance, you’re not really changing anything,” he says.

What clearly sustains McGorry is what drew him to psychiatry in the first place: a passion for the people and the beneficial nature of his work.

He still spends one day a week working at one of Melbourne’s headspace centres and visits the Coffs Harbour headspace in New South Wales once a month.

“You see people go through tough times, and then you see them getting better, and that gives you incredible satisfaction,” he says.

“I overwhelmingly feel a great sense of gratitude to be able to make a change.”