Loading component...

At a glance

By Jenni Davis

If you want to change the face of a city or even an entire country, one of the most popular ways to do it is through “megaprojects”.

These are huge, complex, multi-billion-dollar investment projects, from China’s high-speed rail network to Sydney’s Opera House, beloved of politicians but with a well-deserved reputation for costing far more than expected.

The most fiscally risky megaproject of all is not a structure but an event: the Olympic Games. This month, Rio de Janeiro becomes the latest city to seek a return on its Games investment.

The Olympics’ track record is startlingly poor.

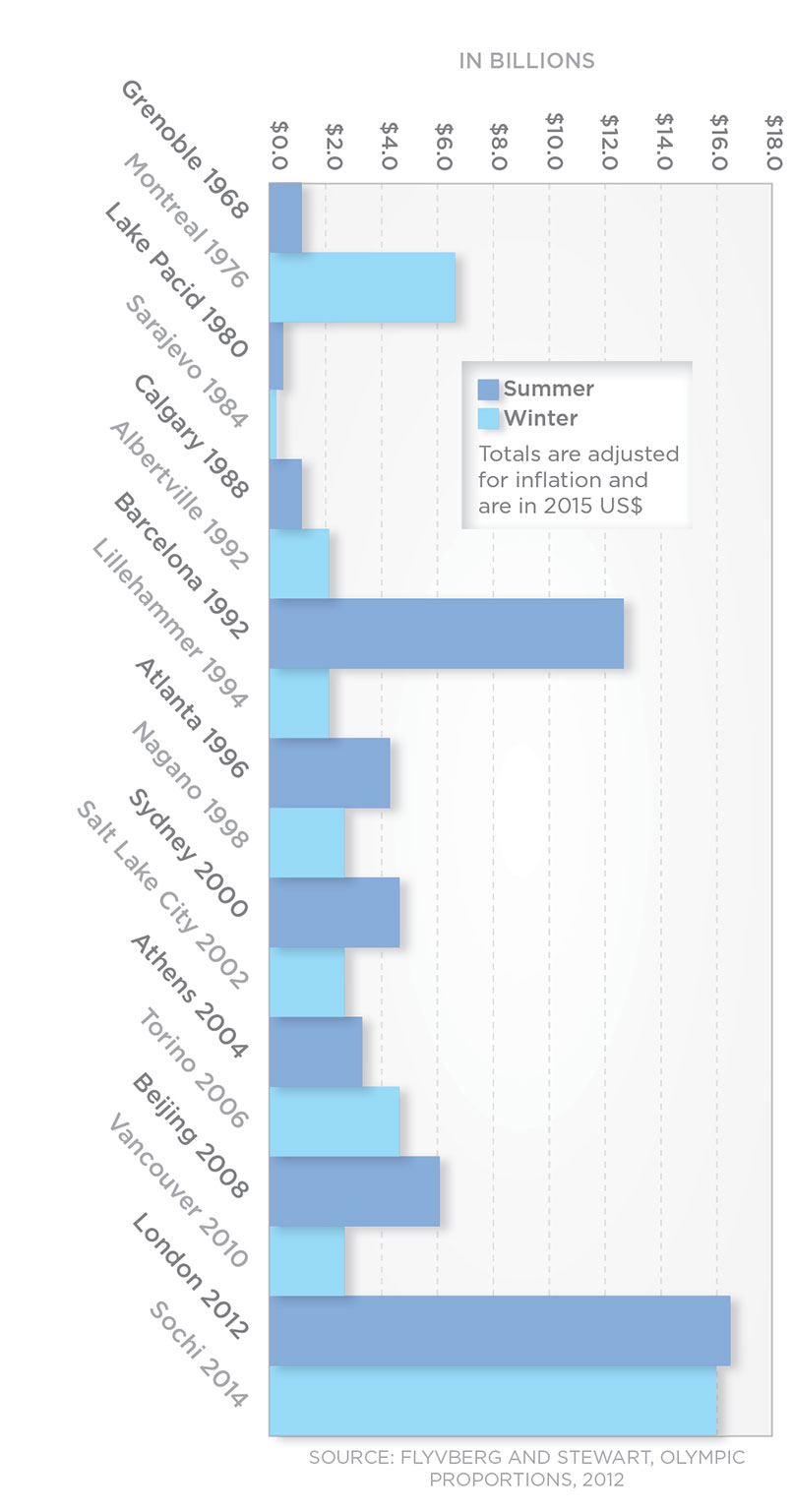

From Montreal in 1976 and Lake Placid in 1980 to Athens in 2004 and London in 2012, both the summer and winter Olympics have blown budgets and frequently left host cities wondering whether it was all worth it.

Bent Flyvbjerg is the world’s leading expert on megaprojects. In the May 2015 INTHEBLACK, he listed the factors that bust megaproject budgets: rushed planning, scope changes, lack of expert leadership, political pressure.

Olympics, Flyvbjerg says, make all of those problems worse.

In 2012, he and colleague Allison Stewart calculated that every Olympics dating back to 1960 went over budget – and rarely by slim margins. They found the average cost overrun in real terms was a staggering 179 per cent.

For the summer Games, that figure stretched to 252 per cent.

“Other project types are typically on budget from time to time,” they wrote, “but not the Olympics … the Games overrun with 100 per cent consistency. No other type of megaproject is this consistent regarding cost overruns.”

What is significant to the spend, and perhaps unique to an Olympics, is that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) insists bidders guarantee that the host city and its government bear the brunt of any cost overruns.

Bidders know this and promise new infrastructure anyway.

Flyvbjerg and Stewart suggest the guarantee is like “writing a blank cheque for a purchase, with the certainty that the cost will be more than has been quoted … A budget is typically established as the maximum – or, alternatively, the expected – value to be spent on a project.

"However, in the Games the budget is more like a fictitious minimum that is consistently overspent.”

When a city is awarded the right to host the Games by the IOC, it takes on what Will Jennings, professor in political science and public policy at the University of Southampton and author of Olympic Risks, describes as the “winner’s curse”.

As Jennings explains, “The bottom line of the winner’s curse is that the bidding process puts pressure on organisers to put a positive spin on what is going to be organised, how much it will cost and what the benefits will be.

"When you look at the planning, there is a tendency for the proposals to be what I call fantasy documents.”

This leads many analysts to say the net economic benefits of hosting an Olympics are negligible at best and are rarely offset by revenue or increases in tourism or business.

Montreal, which was host city in 1976, remains the gold standard for how not to host an Olympic Games.

The city’s then mayor, John Drapeau, set the standard for political claims by declaring that a deficit was as likely as a man having a baby.

The main stadium was an engineering feat that left the city with a US$1.48 billion debt. The Games as a whole ended up nearly 800 per cent over budget and took the city 30 years to pay off.

The silver medal for cost overruns goes to Barcelona for its summer Games in 1992, which went 417 per cent over budget, while the 1980 winter Games at Lake Placid, US, at 321 per cent over budget, takes the bronze.

Why the Olympic-sized blowouts?

Flyvbjerg says it’s “shockingly normal” to find large projects being managed with little review. An Olympics only amplifies that standard.

The deadline of an opening ceremony attended by thousands and watched by hundreds of millions does not give Games organisers the luxury of time to go over their plans and change tack. Sometimes, things just need to get done.

Andrew Zimbalist, professor of economics at Smith College in Massachusetts and author of Circus Maximus: The Economic Gamble behind Hosting the Olympics and the World Cup, lays part of the blame at the hands of the IOC.

Zimbalist describes the body as an unregulated monopolist that holds all the cards in the Olympic bidding process.

“Generally speaking, the cities fall over themselves to appeal to the IOC and end up spending US$15-20 billion or more to host the Games,” he says.

“If it’s the summer Games, they end up bringing in [only] about US$4-5 billion. That experience is pretty universal. There are a few exceptions, but the general financial balance is not at all favourable.”

Olympic organising committees and cities’ political elites cite infrastructure gains as one of their most compelling reasons to spend vast sums of city money.

They promise that accommodation built to house athletes will become community housing, that stadiums will play host to lucrative sporting fixtures long after the closing ceremony, and that new rail lines will boost city transport.

They tout projections of increases in economic activity and increased tourism.

Political leaders like Boris Johnson, mayor of London during the 2012 summer Games, argue that Olympic dividends are not reaped immediately, but over years.

The reality is consistently different.

Athens exemplifies the problem, with many venues now abandoned and locked behind fences and Greece suffering a long economic downturn to which its Olympic debts have contributed.

Beijing’s famous Bird’s Nest stadium is a favourite on the sporting tourist trail but is still looking for a regular tenant. Building it cost around US$480 million and it costs US$11 million a year to maintain.

John Madden, a professor at Victoria University’s Centre of Policy Studies in Melbourne, assessed the economics of the Sydney Games and found that they reduced household consumption in Australia by A$2.1 billion, all while failing to increase employment or boost post-Games tourism.

“All the studies we did after the Games suggested that we were no more on the tourism map than we were before the Games,” he says.

The exceptions are Barcelona and Los Angeles. LA used a unique environment to negotiate an economically sound plan; Barcelona used the Olympics to deliver on an existing long-term plan for the city’s remodelling.

Why continue to invest in the Olympics?

With such consistent cost blowouts that place a huge burden on regional and national economies, why do nations continue to invest in these sporting megaprojects?

The spirit of the Olympic movement is one overriding answer.

For decades, when challenged about cost overruns, organisers and politicians have talked of the power of the Olympic Games to unify the world – geopolitical conflicts are not relevant on the track or in the swimming pool.

During the Olympic Games, national pride is often at a high point in the host city. A BBC survey conducted after the London Games showed that more than two-thirds of Britons believed the estimated cost of £8.77 billion was well worth it.

Victor Matheson, professor of economics at College of Holy Cross in Massachusetts and a specialist in the economics of sporting events, says civic pride tends to bloom during these extended competitions.

“In the 2006 World Cup held in Germany, economists found no significant increases in economic activity or tourism,” he says, “but there was a clear and marked increase in the self-reported happiness of Germans after the event.”

Madden also cites civic pride as a positive outcome of hosting an Olympic Games. “The Sydney Games were probably not a cost to society because people enjoyed them, and if you want enjoyment, you pay for it,” he says.

“You’re not going to get this double dividend of enjoyment of the Games plus an economic boost. The Olympics fall into a class of investments where benefits are non-economic.” The excitement of an Olympics has no dollar figure attached, but it is still real.

Beyond all that, too often forgotten, is the simple value of sport itself. Sportspeople like gymnast Nadia Comaneci, scoring perfect 10s at Montreal, and swimmer Michael Phelps, with his eight Beijing gold medals, provide wonderful models that inspire not just elite athletes but young athletes everywhere.

Matheson, however, notes one more non-economic, human-centred factor: political gain.

“If you’re a politician, you like to be in the centre of attention and there’s nothing like the Olympics to put you there,” he says.

“I think that’s the argument you can make for Vladimir Putin spending US$51 billion on the Sochi Olympic Games. This wasn’t about making money for Russia.”

And the future...

The London Games were around three times as expensive as Beijing four years earlier. The Sochi spending two years later made the budgetary issues impossible to ignore.

The budget for this year’s Rio Olympics is US$11 billion less than London’s, yet still includes substantial public infrastructure.

IOC vice-president John Coates says the IOC doesn’t want cities to build anything that won’t be sustainable and can’t be justified. Rio has made public transport accessible to 63 per cent of the city, he says, up from 17 per cent when Games work began.

The IOC has also agreed to “actively promote the maximum use of existing facilities” and to use facilities outside host cities.

Such moves have cut US$1.8 billion from Tokyo’s 2020 summer Games hosting costs, says Coates. Basketball, for instance, will be played at a venue an hour from Tokyo.

“We don’t want any white elephants – and that’s probably the criticism of Athens,” he explains. “We are now looking at 2024 and three of the four cities [Paris, LA and Rome] have very little to build.”

Jennings says the Olympics will benefit from the IOC’s reduced appetite for risk.

“They have sharpened up their consideration of risk in how they select a host city and they go through a much more comprehensive evaluation of city bids,” he says.

Yet given Brazil’s economic woes – exacerbated by the mosquito-borne Zika virus infecting thousands across the country – Jennings questions the decision to award an Olympics to emerging economies.

“[It] raises a whole other set of risks that aren’t faced by more advanced economies, whether it’s construction standards, corruption, public health, you name it,” he says. The Games now go to nations like Brazil, he adds, because such events have “saturated the markets” of advanced economies.

With such dismal measurable economics, the Rio Olympic Games will need to rely even more on the brilliance of the athleticism on display, and the entertainment and inspiration it brings to a global audience.

The price of Olympic security

All Olympic Games since the 9/11 terror attacks in the US have paid a huge price for security, an outlay that did not trouble the balance sheet for earlier Games.

The 1972 Munich Games were, of course, tarnished by the attack that killed 11 Israeli Olympic team members and one German policeman, but the perceived threat of terrorism has surged in the past 15 years.

Economist Victor Matheson, who specialises in the economics of sporting events, notes that while Sydney spent US$250 million on security for the Games in 2000, just four years later Athens spent US$1.4 billion.

“The difference is that September 11 happened in between,” says Matheson.

“When you have to spend what amounts to be about US$100 per spectator just to keep those spectators safe, there’s no way you can have a Games that makes money overall for a country.”

How Los Angeles and Barcelona broke the winner's curse

In the past three decades, two Olympic Games stand out for economists for their overall net gains.

When the bidding opened for the 1984 Olympics, Los Angeles was the only city to express interest. After Munich’s terrorism, Montreal’s cost overruns and Moscow’s boycotts, most countries shied away.

The US city exploited its unique negotiating position: it would host only if it could use existing facilities from 1932’s previous LA Games and house athletes in university dormitories. Economist Andrew Zimbalist says the city ended the Games with a US$250 million surplus.

Despite exceeding its budget by more than 400 per cent in 1992, Barcelona also reaped long-term benefits from the Games. The city wanted to reorient itself and open up to the sea.

“Barcelona reversed the normal sequence,” says Zimbalist.

“They had a plan first and then they took on the Olympics as part of it. They used the Olympics as an excuse to redesign the tourist infrastructure and redesign their ports to be tourist friendly.”