Loading component...

At a glance

- Members of Australian superannuation funds pay A$30 billion a year in fees – among the highest charges in the world.

- Of the 190 regulated funds, almost half have less than A$1 billion in assets and have above average operating costs.

- A 0.5 percentage point rise in fees is estimated to shrink a member's retirement savings by 12 per cent over the course of their life.

- The Productivity Commission estimates savings of A$1.8 billion a year if the 50 highest-cost funds merged with 10 of the most efficient funds.

Australian superannuation fund members are hit with some of the highest charges in the world.

Super funds collect a hefty A$30 billion a year in fees, and cross-country comparisons show that Australian retail funds, operated by banks and other finance companies, are particularly pricey.

As Brendan Coates, household finances program director at the Grattan Institute think tank puts it, “Australians are spending more on having their superannuation managed than they are on energy bills”.

Through a mix of administrative and investment fees, indirect costs and service charges, some funds are levying fees equivalent to 1.5 per cent or more of assets, which is substantially more than the average 0.9 per cent of assets charged by not-for-profits, and in the top bracket of charges internationally.

Differences in regulation, taxation, reporting requirements, administration practices and disclosure between jurisdictions mean international comparisons are complex and tricky to make.

Nevertheless, an analysis of 51 pension schemes in 31 countries undertaken by the International Organisation of Pension Supervisors (IOPS) found that fees charged by Australian retail funds were among the heaviest.

The impact of these imposts on retirement incomes can be significant.

The Productivity Commission believes that every 0.5 percentage point increase in fees shrinks the retirement nest egg of a typical fund member by 12 per cent over the course of their working life – the equivalent of two years’ lost pay for someone on a starting salary of A$50,000.

A costly investment

A large part of the problem is down to shortcomings in the very structure of the industry that undermine competition and efficiency, Coates says.

Requiring people to choose from among dozens of products when the pay-off may not come for 40 years promotes disengagement and is “a recipe for failure”, he says.

His concerns are backed by evidence that less than 10 per cent of members switch between funds and products each year, and only a third have ever changed their investment option.

“Competition requires people to make informed choices,” Coates says. “There is no competition now because there is no informed choice.”

The durability of small super funds is seen as another telling sign of inadequate competition.

“If you have an industry with 15 to 20 players at most, you’ve got plenty of competition,” Coates says.

“When you have 100 players, that’s a sign you haven’t got enough competition to winnow out the poor performers.” Some funds are levying fees equivalent to 1.5 per cent or more of assets, which is substantially more than the average 0.9 per cent of assets charged by not-for-profits.

There are currently 190 funds regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), almost half of which have less than A$1 billion in assets and, due to their size, have above-average operating costs that eat into member balances.

There has been some consolidation of funds over the years as operators have pursued economies of scale.

In its Superannuation: Assessing Efficiency and Competitiveness report, the Productivity Commission calculates that since 2004, more than A$4.5 billion has been saved in reduced administration costs and other expenses arising from mergers and acquisitions.

However, Commissioner Angela McRae, who coauthored the report, says muted market pressure has meant only a fraction of these savings has been passed on to members in lower fees and higher returns.

The Productivity Commission states that at least a further A$1.8 billion a year could be saved if the 50 highest-cost funds merged with 10 of the most efficient funds, delivering an extra A$22,000, on average, to members at retirement.

A costly legacy

It is not only smaller, less-efficient funds weighing on member returns. There is a long trail of high-fee legacy products – closed to new members, but still operating – dogging the industry.

The Productivity Commission believes the retirement savings of about four million Australians, worth A$275 billion, are tied up in such accounts.

These schemes have an average fee of 2.2 per cent of assets, typically including high administration and investment charges, as well as trailing commissions and elevated financial advice service costs. Until now, funds have dragged their feet in alerting members to lower cost alternatives.

Camille Schmidt, market insights manager at SuperRatings, says these legacy products are part of the reason why retail funds have significantly higher administration fees (an average of 0.5 of a percentage point) than not-for-profit funds (0.16 of a percentage point).

Promisingly for investors, retail fund administration charges are coming down as operators become more efficient and legacy products disappear, but the process is painfully slow.

At the same time, costs for industry funds are rising.

Schmidt warns that not-for-profit funds will come under increasing pressure from recent changes allowing for the automatic consolidation of low-balance accounts.

“A lot of them will be losing a significant proportion of their membership, and they will lose the member fees they were able to charge to those members,” she says. One large fund has already responded by lifting its fees for remaining members.

Unhappy returns

Of course, investors may accept high fees if their fund delivers strong returns, but the evidence is that the opposite is often the case.

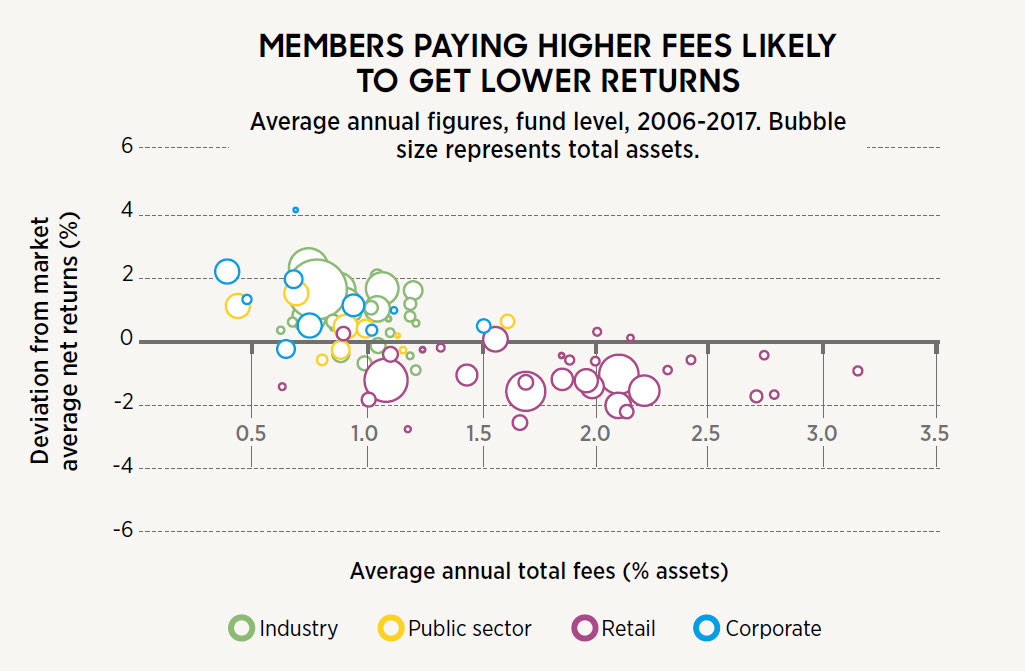

A Productivity Commission analysis of returns from 87 funds with A$1 trillion in assets found that in the 11 years to 2017, those charging higher fees delivered lower returns, on average, than cheaper funds.

“That was a fundamental finding, and very surprising,” McRae says. “You would absolutely expect the opposite to be the case.”

Even expensive funds with higher net returns do not significantly outperform less costly rivals once the cost of risk is taken into account.

Under pressure

Heeding concerns about elevated fees, the government has enacted laws that ban exit fees, cap charges on balances of less than A$6000, give authority to consolidate low-balance accounts and cancel insurance attached to accounts inactive for 16 months or longer.

Even before these changes came into effect, investors were already voting with their pay packets.

The flow of money to higher-fee retail funds has slowed to a trickle.

In the year to June, retail fund assets grew by just 0.5 per cent to A$625.7 billion, while funds directed into lower-fee industry funds surged 13.8 per cent to reach A$718.7 billion.

With A$30 billion of revenue from fees at stake, however, Coates expects funds to fight hard against fee-reducing reforms.

“The high fees collected from members are the revenue of the industry, so there’s lots at stake to ensure those revenues don’t disappear,” he says. “It is incumbent upon government to do what is right for super fund members, particularly when they are compelling them to save a tenth of their wage.”