Loading component...

At a glance

- The dark web is the online equivalent of the black market. Websites listed on the dark web cannot be accessed by standard search engines.

- The dark web takes up about 5 per cent of the entire internet ecosphere, but its annual value is estimated at between US$1-2 trillion (A$1.3-2.7 trillion).

- Businesses that have undergone rapid digital transformation due to the pandemic need to prioritise the task of assessing and addressing their cyber vulnerabilities.

In January 2021, a police sting on the German-Danish border resulted in the arrest of a 34-year-old Australian who is alleged to have operated one of the world’s largest illegal online marketplaces.

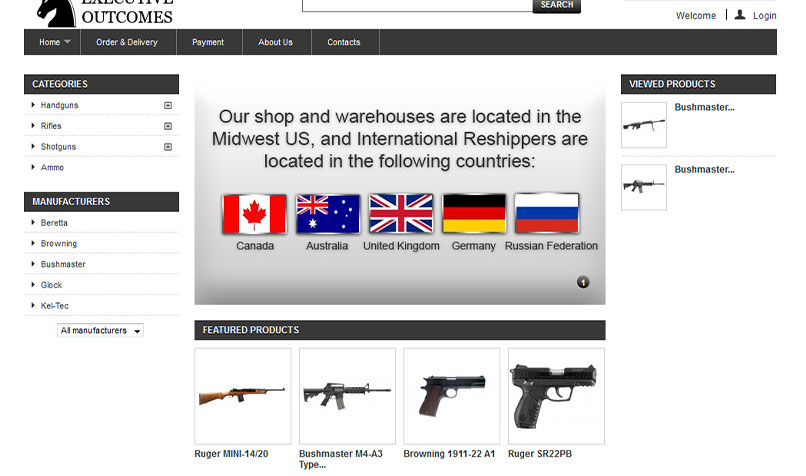

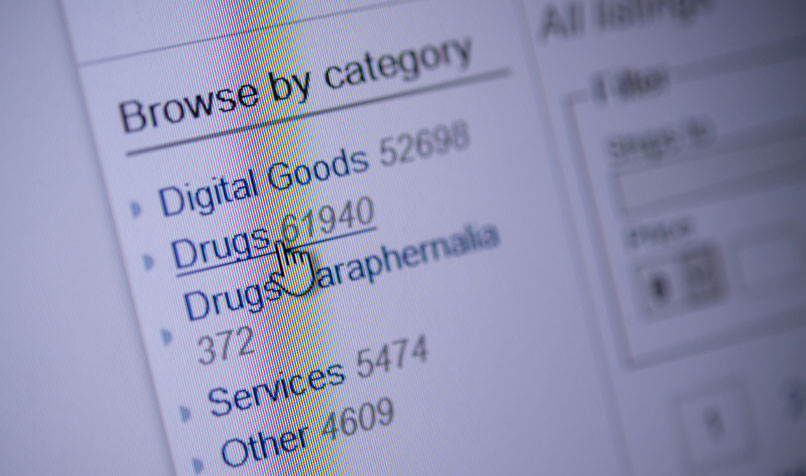

DarkMarket, as it was known, existed on the dark web and had half a million users and 2400 vendors, who sold everything from drugs to counterfeit passports and stolen credit card data. The website had an estimated value of A$220 million, mainly in Bitcoin and Monero cryptocurrencies.

While the takedown of DarkMarket was significant, the reality is that “Julian K”, as its alleged operator was identified by police, is one of the very few dark web “powerhouses” to have been caught.

Cybercriminals operate on the dark web with near impunity, says Tom Kellermann, who heads cybersecurity strategy for VMware in the US.

Kellermann also sits on a newly created cyber investigations advisory board with the United States Secret Service, which is helping the agency to modernise its efforts in dealing with financial crime.

“Despite the fact that cybercrime is the number one priority of law enforcement officials globally, only 2 per cent of online bank heists result in a successful prosecution, and the average theft is valued at US$6 million [A$8 million],” Kellermann says.

“If you rob a bank at gunpoint in the US, there is a 97 per cent likelihood that you’ll be arrested and, on average, you’ll steal about US$10,000 [A$13,600],” he says, quoting figures provided by the Secret Service.

What is the dark web?

The dark web is the online equivalent of the black market. Most people will never see or interact with it because it is intentionally hidden and access to it requires a specialised browser.

The most common browser is called TOR, which is also known as the “The Onion Router”. In Australia and New Zealand, it is not illegal to access the TOR network – but accessing its forums can be.

“It is no different to if you were trying to buy or sell something illegally in real life. The same laws apply to you,” says Josh Lemon, a certified instructor at the cybersecurity and training facility, the SANS Institute.

On the dark web, cybercriminals can create websites that cannot be indexed (that is to say, searched) by standard search engines such as Google.

Other anonymising technologies, such as virtual private networks (VPNs), are also used to hide information about users, such as their geographic location.

Payments on the dark web are made using cryptocurrencies, and illegally obtained goods are often delivered using gig worker delivery services, which are harder to trace than the postal service.

Think of the entire internet ecosphere as an iceberg. The “world wide web” that we are familiar with comprises just the top 5 per cent of the iceberg – the visible part.

Beneath the water is the “deep web”, which accounts for about 90 per cent of the world’s websites. Below the deep web is the “dark web”, which makes up between 5 and 10 per cent of the iceberg.

The terms “deep web” and “dark web” are often used interchangeably, but this is incorrect. What they have in common is that websites on both are not indexed.

However, much of the content on the vast deep web is legitimate and legal.

We use the deep web when we are doing online banking, using a private social media account, a company intranet or accessing our medical details – in other words, the deep web is all websites that require access through a dedicated channel.

Some people prefer the privacy the deep web affords and for their browsing histories not to be tracked.

The New York Times hosts its website on the deep web, so that people in countries where access to the web is heavily censored can still access its content.

Considering the relatively small size of the dark web, its value is staggering. Estimates put it at somewhere between US$1 trillion (A$1.3 trillion) and US$2 trillion (A$2.7 trillion) annually.

Boom time during the pandemic

The dark web was invented in the 1990s, as part of a research project by the United States Navy, which sought a means of providing confidential transmissions over the internet.

A decade later, researchers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) opened the dark web to people outside of the military. The invention of cryptocurrency helped the dark web flourish, because it added a new layer of anonymity to transactions.

"Think about securing your data as if you're securing the crown jewels - the most precious asset that belongs to your orgnisation"

During the first wave of widespread COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020, the number of dark web forum users grew by 44 per cent, according to Israeli cyber intelligence company Sixgill.

There were several reasons for this, chief among them being that street crime became harder to execute due to the lockdowns.

Just as many criminals took their businesses online for the first time, the mass shift to working from home compromised organisations’ cybersecurity levels, creating a perfect cyberstorm.

Corporate victims

Cybercriminals on the dark web target corporations by stealing confidential data and then putting it up for sale.

According to Dr Campbell Wilson, senior lecturer and associate dean at the Faculty of Information Technology at Monash University, who conducted a targeted crawl of the dark web in 2017 with permission from the Australian Federal Police, 7.5 per cent of the illegal content on the dark web is stolen corporate data.

One of the most popular types of corporate data bought and sold on the dark web is login credentials.

“The organisation often doesn’t know that anything has been stolen until they either detect something going wrong inside their organisation, or they are notified by law enforcement officers,” says Clarence Chan, digital trust and cybersecurity director with PwC Malaysia.

To find out if they have been compromised – or are at imminent risk of doing so – organisations need to enlist the help of a specialist third party. That’s because access to dark web forums is restricted to users who have gone through a vetting process.

“You may need to hack another organisation and provide evidence of it, or produce malware that you then submit to the forum so that everyone else can see it. That will give you enough status to be admitted,” says Lemon.

Chan says, “We carry out searches through what is called a ‘threat intelligence platform’, which has access to some of these dark web sources. We try to find out whether a particular company has had their information breached and if that information is already up for sale.”

He cites the example of a company whose data was recently put up for sale. PwC received an alert from an intelligence threat platform that it subscribes to and was able to inform the company immediately.

“The cybercriminals might put out just a snippet of the data set…to entice a buyer. Sometimes it’s a scam and they don’t really have the data, or they may have just a subset of it.”

Chan says that companies that store their data in the cloud without configuring it properly can leave themselves exposed.

“Think about securing your data as if you’re securing the crown jewels – the most precious asset that belongs to your organisation. If you cannot afford to lose your data, spend more time, effort and funds on protecting it.”

A game of cat and mouse

While much research has been undertaken on how to unmask a cybercriminal on the dark web, policing the ephemeral and global cybercrime cartels has proven notoriously difficult.

“The scourge of cybercrime can only be tackled by disrupting the fundamental business model, which relies on anonymous payments,” says Kellermann. “You need to disrupt the flow of money and undermine the trust between these groups, so that they turn on each other and it’s no longer a lucrative endeavour.”

He argues that greater regulation of digital currencies is imperative. “I’m not saying that virtual currencies created the epidemic of ransomware, but the majority of cybercrime proceeds are laundered through virtual currencies.”

At a minimum, he says the rules in the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on Money Laundering need to be modernised so that an entity that is providing a virtual currency has the capacity to disrupt or freeze any capital when called upon by law enforcement.

"People say that we don't have the resources to go after cybercriminals. Why not take the proceeds of crime on the dark web?"

“Right now, these entities are just turning a blind eye to their digital currency being used for nefarious reasons, because there’s no pressure on them to do anything,” says Kellermann.

He argues that policing could be far more effective if the money seized from the dark web was used to fund critical infrastructure protection.

“People say that we don’t have the resources to go after cybercriminals. Why not take the proceeds of crime on the dark web? When law enforcement agencies take down a big drug kingpin, they seize their house, cars and cash, and those assets are redistributed to fund law enforcement activity. There’s no real difference here with the dark web.”

One of the challenges is tracing the money, which is laundered multiple times in a short space of time. Another challenge in catching the criminals themselves is the protection they receive from some government regimes.

“These rogue nation states truly embrace their cybercriminals as national assets,” says Kellermann. “They have made them untouchable from Western law enforcement.”

Upskill now

How to protect your organisation

As the first line of defence against cybercriminals, Lemon recommends enlisting a cybersecurity firm to monitor activity on your organisation’s behalf.

“They’ll do things like keep an eye on keywords, email addresses or IP addresses that might relate to your organisation.

“Some of these forums require a high level of trust. Someone might say that they have access to something relating to Company XYZ, but it takes a level of interaction with the criminal to actually understand what it is that they’re selling,” says Lemon.

Employees at all levels of the organisation need to receive cybersecurity training, including being aware of their web browsing behaviour, because cybercriminals often steal login information by masking a fake website as a legitimate one.

Training should also focus on safety around what can and cannot be installed on work computers, and making sure any downloads come from a legitimate source. Another tip is to implement two-factor authentication, because it means that simply stealing login details will not result in access.