Loading component...

At a glance

- In most OECD countries, middle-class income growth has been below average.

- The middle class sustains consumption and drives investment – a squeezed middle class spells trouble for an economy at large.

- Australia’s middle class suffers from rising costs and stagnant incomes, and there’s a lack of vision and policy to boost and maintain financial security.

By Jessica Mudditt

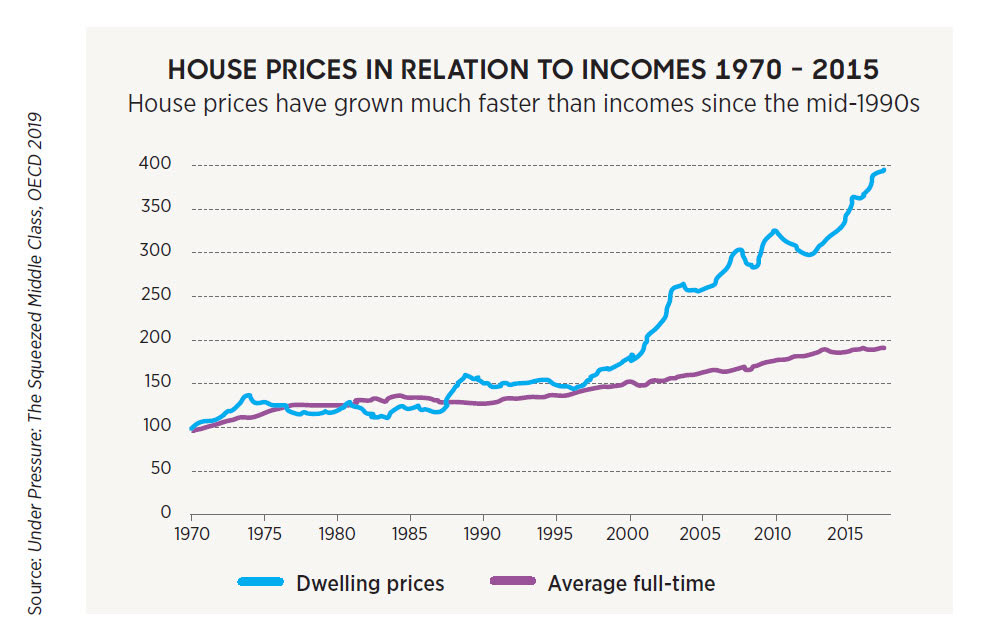

The middle classes in developed nations around the world are feeling the squeeze. Prices are rising, but income growth is stagnant. Put simply, life is becoming more expensive.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) says the middle-class dream is increasingly only a dream for many, and the trend is worrying.

“A strong and prosperous middle class is crucial for any successful economy and cohesive society,” it says in a report analysing the phenomenon.

“The middle class sustains consumption, it drives much of the investment in education, health and housing, and it plays a key role in supporting social protection systems through its tax contributions.”

Incomes are stagnating

In many of the OECD’s 36 member countries, middle incomes have grown less than the average – in some there has been no growth. This is largely due to technological changes. Many middle-skilled jobs have been automated, which is bad news for the middle-class workers who traditionally carried them out, says Sarah Hunter, BIS Oxford Economics chief economist.

“Technological progress in the recent past has tended to favour relatively highly skilled labour. For example, the benefits of having information at your fingertips are larger if you work as a professional. As a result, growth in their wages has outstripped other types of employment, and these occupations tend to be relatively highly paid.

Furthermore, globalisation drives the trend towards outsourcing, resulting in many middle-income jobs being shifted to countries with lower production costs. The end of car production in Australia in 2017 is a symbolic example of this, Hunter says.

All this means that for many middle-income households, saving is difficult and debt is growing. According to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, debt growth is outpacing that of incomes and assets. The proportion of households who are over-indebted rose from 21 per cent in 2003-2004 to 29 per cent in 2015-2016.

Who is the middle class?

What constitutes the middle class is hotly contested and at times politically charged; however, the OECD defines it as households earning between 75 per cent and 200 per cent of the median national income.

The study found that the share of people in middle-income households fell from 64 per cent to 61 per cent between the mid-1980s and the mid-2010s.

“In Australia, it’s even lower, at 58 per cent,” says Jason Pallant, marketing lecturer at Swinburne University.

“While the shift in terms of real percentages may not appear major, when you consider that it represents millions of people, it is actually a big issue.

“It signifies that the rich are getting richer, while the people in the middle are really struggling. Many are not going up from the middle class, but down.”

Australian story

The OECD has identified significant broad trends, but the situation in Australia is more nuanced, says Jarrod Ball, Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) chief economist.

“We had really strong income growth right up until the peak of the mining boom in 2012,” Ball says.

“Since then, incomes have been stagnating across all income groups.

“Costs have been growing rapidly in terms of housing, energy, child care and education. When you put together stagnating incomes and these rapidly rising costs, it is easy to understand why many middle-income earners are feeling the squeeze.”

Ball says that growing wealth among the top tier of earners is more extreme in the US.

“One of the reasons we’ve done better in Australia is because of our policy settings for providing basic support, such as universal education and public health services. I don’t think it’s inevitable that the middle class will shrink further if governments really make sure there is a safety net.”

Addressing housing affordability will also be imperative.

“Twenty-five years ago, owning your own home was just something people did: you grew up and you bought a house. That is no longer the case,” says Deloitte partner Nicki Hutley.

Hutley says the flow of people to cities in search of higher-paying jobs pushes up house prices. The number of people under housing stress, which is typically defined as those who are paying 30 per cent or more of their income towards housing, is increasing, not just in Australia, but around the world.

“We commonly talk about homelessness being predominantly driven by social issues, particularly mental health issues, but we are increasingly hearing about older women having to sleep in their cars because they haven’t got enough superannuation to carry them through their retirement, and the pension will not cover the cost of their accommodation,” Hutley says.

“In one of the world’s richest nations, it doesn’t seem logical that this should happen.”

The decline of the department store

The shrinking middle class has also contributed to a sluggish retail sector globally.

“People simply have less discretionary income and therefore less ability to go out and buy things,” Pallant says.

The result is what’s known as retail bifurcation. Retailers positioned as either luxury or value-based are performing well, while those in the middle are struggling. The situation for department stores is particularly bad, as they are neither luxury nor discount in their offering.

“It mirrors what’s happening with the middle class: those at the top and those at the bottom are growing, while the ones in the middle are really struggling,” Pallant says.

He emphasises that this is not the only reason for department stores’ woes. Shoppers’ expectations have increased, as has their exposure to global brands backed by economies of scale. Meanwhile, department stores haven’t evolved to meet these challenges.

“There are complaints around customer service and products being out of stock, but it is fair to say that the retail industry is mirroring broader societal shifts.”

What can be done?

Policy initiatives aimed at protecting middle-class living standards and financial security are needed, but are complex and require long-term vision and political will.

“These issues will be exacerbated if we don’t change policies,” says Hutley.

“But I do think people are increasingly recognising the challenges faced by many Australians, and voices are getting louder around things like housing affordability. I believe that Australia has the heart and mind to deal with these problems.

China faces different challenges

China's growing middle class and Hong Kong's 'sandwich' class

While economists disagree about whether China is now a developed nation, most acknowledge that its middle class has been growing at a substantial pace.

“In terms of China’s total economy – just the sheer size of it – you could say it is now a developed nation.

"However, if you think about it in terms of per capita GDP, it still has a long way to go, especially compared with economies like the United States,” CEDA's Ball says.

China is undergoing rapid urbanisation, with people flocking from rural areas to cities where their employment prospects are better.

This is considered the largest human migration in history, with almost half of the population now living in cities. Despite this, China too faces a slowing economy, and the lack of welfare safety nets in comparison to many Western countries makes life precarious for millions – even those in its middle class.

“China faces a different set of challenges. Certainly, as you see more and more people coming into the Chinese middle class, there will be challenges around how you ensure that people still feel like the standards of living are rising,” Ball says.

The economic opportunities for Australia from this growing class of consumers are vast, according to Drew Waters, the director of strategic partnerships at Asialink Business and the former head of the Australian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong.

“China’s growing middle class provides some great markets for the rest of the world, who will satisfy the needs of that new middle class,” Waters says.

“Australia will benefit from this – China is already Australia’s largest export market and the majority of our exports are goods or services that are consumed by the growing middle class.”

Change is also afoot in Hong Kong, although a different phenomenon known as the “sandwich class” has emerged. While incomes in Hong Kong have long been enormously varied, this term has popped up to describe a group of the city’s lower middle class who fall into an awkward spot.

They earn above the average median wage and so are not poor, but they are unlikely to pass mortgage tests imposed by lenders and also fall short of qualifying for subsidies. Also, median real estate prices in Hong Kong are among the most expensive in the world and wages are not keeping pace.

“Half the population of Hong Kong lives in public housing and there is a huge waiting list of a quarter of a million people and an average waiting time of about five years,” Waters says.

“The Hong Kong government has started undertaking initiatives to de-stress housing prices, including by making more land available for public housing.”