Loading component...

At a glance

- Economists believe politicians tend to delay admitting to a recession until it is in full swing, meaning that anti-recession measures are usually delivered too little, too late.

- More than a decade after the 2008-2009 recession, economists are contemplating the next recession and how its impact might be minimised.

- Economists suggest that authorities may need to consider a simpler fiscal policy of distributing money directly to citizens by cutting taxes or increasing welfare payments, or both.

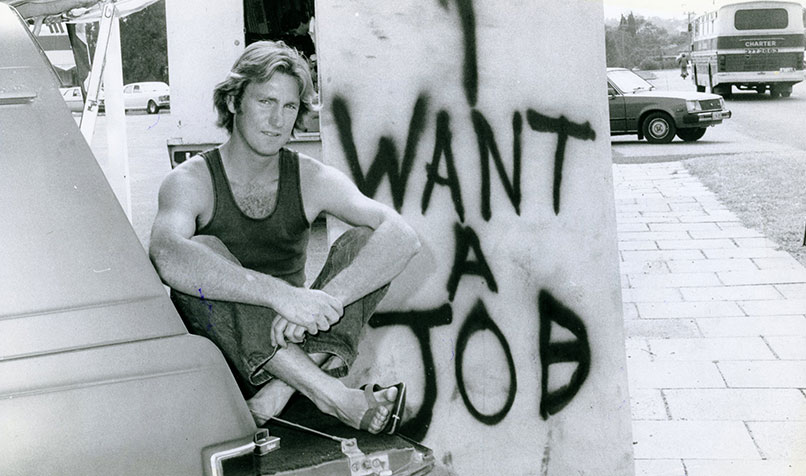

Recessions leave deep scars on the lives of people who lose their incomes as the economy stops growing and unemployment soars. For the macroeconomists who must try to lessen their effects, recessions are a challenge still partly unsolved. Many economists would like politicians to think more about recessions while times are still good.

Melbourne Business School dean, Professor Ian Harper, says Australian economic authorities aim to avoid recessions “like the plague”. Former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has nominated “contingency plans for the next recession” as among the most urgent economic steps governments should be taking.

Yet in practice, governments rarely make such plans, and almost never react as a recession hits. Instead, responding to recessions is usually a very slow and messy business.

Nicholas Gruen, an economist who advised former Australian treasurer John Dawkins in the early 1990s, recalls the process of assembling the Keating government’s One Nation stimulus package. After rejecting most of the spending suggestions, Gruen says, the Australian Treasury realised late in the process that the package contained barely enough economic stimulus for anyone to notice – just one-quarter of 1 per cent of GDP.

Gruen himself suggested adding an additional family allowance payment.

“Treasury had a fit at that, said it didn’t send the right signals,” he recalls. “But they got over that when Dawkins liked it, and we did it.”

Yet that still only took the package’s immediate stimulus to half of 1 per cent. Gruen says that “it was obvious that we needed a lot more than that”.

Lindsay Tanner, who would go on to become Australia’s finance minister from 2007 to 2010, used to recount a story of concrete railway sleepers stacked high for track-laying projects to help end the 1990-1991 recession. His problem with this strategy? By the time the sleepers appeared, the year was 1995 and the recession was long gone.

The stimulus challenge

These real-world accounts sum up many of the problems economists and policymakers face in trying to devise recession-busting stimulus. Even if they work in theory – which not all economists accept – anti-recession measures have usually delivered too little, too late.

Two US economists, Doug Elmendorf and Jason Furman, argued even before the global financial crisis (GFC) that effective fiscal stimulus must be “timely, targeted and temporary”.

Yet politics makes all three difficult.

Now, more than a decade after the crisis of 2008-2009, more and more economists are thinking about the next recession. They’re asking how we might minimise its impact, and how we might avoid the mistakes Gruen and Tanner have described.

Finding answers, though, is even less easy than in the past.

Interest rates: low on ammunition

One traditional route is to lower interest rates. In the 2008-2009 crisis, central banks did just that, following the advice delivered almost 50 years earlier by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz. They also expanded monetary policy through quantitative easing.

Sarah Hunter, chief economist at BIS Oxford Economics, speaks for most economists when she says aggressive monetary policy in the US helped to prevent a meltdown in the financial system and ease the recession’s effects.

As consulting economist Saul Eslake points out, interest rates seem an attractive lever – central banks can take action right away, while governments must initiate the sometimes slow process of passing budgets and other laws.

However, central banks have new constraints in today’s low-interest-rate world. Having cut official rates in the GFC, they haven’t been able to get them back up. Australia’s official rate, for instance, is now 0.75 per cent; others are even lower, with Japan’s official short-term interest rate target at -0.1 per cent.

As economists put it, many official rates are near or at “the zero lower bound”. One traditional route is to lower interest rates. In the 2008-2009 crisis, central banks did just that, following the advice delivered almost 50 years earlier by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz.

Harper, a member of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) board, but not speaking here on its behalf, says the “zero lower bound” does not mean that central banks have run out of ammunition.

“The RBA can put the cash interest rate where it wants to put it,” he says.

Harper notes that the RBA can also buy other assets, such as government securities or mortgage backed securities – a technique that is known as quantitative easing (QE).

However, Harper agrees that the case for QE is less convincing in a common-or-garden business cycle recession than in a financial crisis. It seems likely that the next recession will be a business cycle recession, where consumption and investment dry up – the most common type of downturn over the past 80 years.

Infrastructure: a long time coming

When a recession hits, governments start looking for infrastructure projects to fund – roads, rail, ports, school buildings, telecommunications and so on. In 2008 and 2009, for instance, incoming US president Barack Obama said “shovel-ready” infrastructure projects would be part of his US stimulus package. This is a specific form of fiscal policy, the government’s spending and revenue raising.

However, Obama ran into the same problem Tanner had noted: infrastructure generally takes years to start. By 2010, Obama was acknowledging just that point.

“The problem,” he told an interviewer, “is that spending ... takes a long time, because there’s really nothing – there’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects.”

Besides, infrastructure no longer deals much in shovels and gangs of men swinging pickaxes. It’s about project management, expensive German or Japanese tunnel-boring machines – and long approval processes.

Australia’s Rudd government tried a smarter version of the infrastructure tactic in 2008-2009. It aimed to use the skills of people no longer employed in home building and forestall the collapse in economic activity that typically follows a building slowdown.

To do that, it rolled out two infrastructure schemes designed to work fast: one scheme built fairly standardised school halls; the second paid to have insulation installed in home roof spaces.

Their economic effect seems to have been positive, but neither scheme was the political success that had been expected. Indeed, the insulation rollout was embroiled in scandal, when four workers died of electrocution.

Cash: beyond handouts

Many economists suggest that in slowdowns, economic authorities may need to turn back to a simpler type of fiscal policy – distributing money, often borrowed, directly to citizens, by cutting taxes or increasing welfare payments or both.

Eslake, Gruen and Harper agree that governments take time passing laws to raise payments or cut taxes. Politicians often resist even admitting the problem until a recession is already in full swing. Few governments have the Rudd government’s 2008 advantage of being able to see a recession approaching from overseas; that allowed a deliberate decision to “get in ahead of the game”, as one Australian public servant put it. Such advance notice comes rarely.

A tough challenge remains when a recession arrives: to get money into the economy quickly, without wasting it. Harper says that for spending to be most effective most often, “it has to be automatic”.

Automating the response

Some of the response already is automatic. In a slowdown, people lose incomes and companies’ profits thin. In each case, their tax burden lightens; individuals may not just stop paying tax, but qualify for unemployment benefits, while companies that make no profit pay no corporate tax.

Economists talk of such mechanisms as an economy’s automatic stabilisers, and they can act just as the tanks and underwater wings of the same name act for ships.

A new book from the US Hamilton Project – Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy – suggests we need more stabilisers that act automatically, by triggering either tax cuts or spending increases driven by rules.

With the right rule you might, for instance, automatically cut income taxes when enough signs appear of a recession taking hold, and restore taxes to their previous level when growth starts again.

Writing in Recession Ready, economist Claudia Sahm even suggests a signal for such an injection of spending power: when the three-month average unemployment rate rises a half percentage point above the low of the prior 12 months.

Another possibility is to have an independent authority administer fiscal policy, just as central banks administer fiscal policy. Gruen, the best-known proponent of such policies, argues it’s a historical accident that most countries have two very different ways of implementing the two different policies, monetary and fiscal, with parliament having to legislate changes in fiscal policy.

Stronger automatic stabilisers and an independent fiscal authority would take politicians out of the loop. Eslake doubts that voters will accept the idea of having spending and taxing decisions put in the hands of either a mechanical rule or an independent authority – even if we’ve already done that with monetary policy.

“By and large,” he says, “decisions about the price of money are qualitatively different from decisions about the nature of the transactions between citizens and their elected government.”

Gruen, however, argues that voters will accept such a move if an effective case is made that it will ease the harsh impact of recessions. After all, Australian politicians “agreed to tariff reform and tax reform” – and both of those, he thinks, were much harder than changing the way a nation runs fiscal policy.

Dodging the recession blow

Years without a recession make citizens less fearful of a recession’s blows. However, those who recall them – such as Eslake, Gruen, Harper, Tanner and the Recession Ready authors – seem deeply affected by the damage they cause. The search for better responses remains, they agree, one of macroeconomics’ most important missions.