Loading component...

At a glance

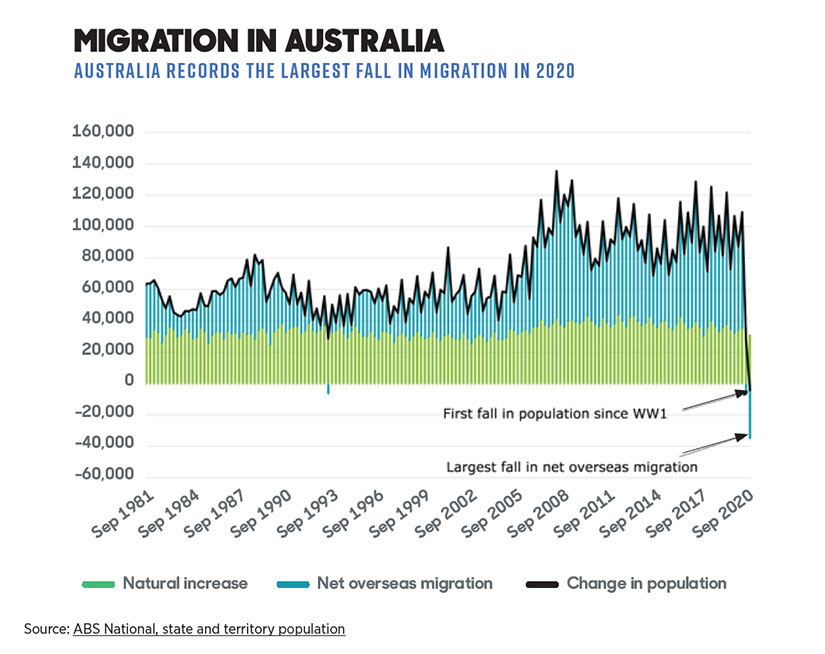

- The pandemic caused a sharp decline in migration to Australia in 2020, resulting in the slowest increase in population since the end of World War I.

- The latest Federal Budget assumes net overseas migration of negative 72,000 in the financial year ending 2021.

- Even with a gradual reopening of international borders, Australia’s total population over the next two years is forecast to be 600,000 less than pre-pandemic estimates.

- Economists point out that a return to 3 per cent economic growth is unlikely without immigration.

By Gary Anders

For decades, population growth has been one of the key drivers of Australia’s economic growth.

That is because growing populations mean more people are spending money across the economy, on everything from housing to consumer goods and services.

In 2020, the Federal Budget assumed the slowest increase in population since the end of World War I, where Australia’s population growth rate has turned negative – largely thanks to a sharp fall in net migration levels.

In addition to reductions in the permanent migration numbers set by the federal government, temporary migration numbers – in the form of tourists, workers allowed to enter Australia on special visas, and international students – have also come to a virtual standstill following the closure of international borders due to COVID-19.

The latest Federal Budget has forecast that net overseas migration will be negative 72,000 in the 2020-2021 financial year. In other words, more people are leaving Australia than arriving.

In 2019-2020, Australia had net overseas migration of 154,000 people, but even this level was well below previous highs of more than 250,000 people a year.

The current negative population trend is set to continue in 2021-2022, with the number of Australians expected to leave the country likely to increase.

“The whole dynamic of population boosting our economic growth is being abruptly disrupted,” says Jarrod Ball, chief economist at the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA).

“There’s no doubt it is going to have a seismic impact on the economy over the next few years.

“When you think about the fact that, by the end of 2022, we will have about one million fewer people in the population than we had been forecasting, that is really significant. It has impacts right across the economy.”

Chris Richardson, partner with Deloitte Access Economics, agrees that the loss of migrants will weigh on economic recovery.

“Even if Australia opens most international borders gradually through 2021, the nation’s total population in just two years is set to be about 600,000 smaller than we’d forecast it to be ahead of COVID-19. That shortfall looks here to stay,” Richardson says.

“If demographics is destiny, then our destiny just got a lot more challenging. That loss of migrants will have impacts for many years – it weighs on the pace of recovery, slowing everything from housing construction to the utilities. And, combined with a slumping birth rate, it will change the outlook for school numbers.”

Rebooting Australian migration numbers

In the latest budget, the federal government has predicted that net migration levels will get back to about 201,000 by 2023-2024.

Ball says that is a good aspiration, but adds it is important to have the right policy settings in place to balance the need for higher migration levels with the need to reduce domestic unemployment.

“While many countries will try to impose permanent migration restrictions in the wake of COVID-19, Australia should resist such policies and promote migration as part of the national economic recovery,” Ball says.

“Migration has been a key driver of Australia’s economic development, and will continue to be so in the decades ahead.”

Anna Boucher, associate professor of public policy and political science at the University of Sydney, says it will be hard for Australia to get back into surplus without increasing migration again.

“Migration is a big part of Australia’s economic success story,” she says. “A return to over 3 per cent economic growth without immigration seems unlikely.”

Boucher says skilled migrants are obviously highly productive and are contributing to the Australian tax base. Other types of migrants, such as international students, provide often more low-skilled labour, but have high consumption, because they are only in the country for short periods of time.

"A return to 3 per cent economic growth without immigration seems unlikely."

“The absence of different kinds of migrants will have different effects. The fewer international students that come means we are not going to have the benefits of those people.

“The economic challenges we are facing are a strong incentive for the government to find creative solutions to bring immigrants back to Australia quickly at previous levels.”

For example, Boucher says about 26,000 people a year are needed to fill horticultural roles, such as fruit picking. The COVID-19 crisis has severely limited the use of this kind of international labour.

“There’s still an ideology that Australians should be put first in times of high unemployment. We need more robust labour market testing,” Boucher says.

“It strikes me that if they can’t deploy people locally and it’s not working moving existing working holidaymakers into those areas, then they will have to look at chartering flights and quarantining, which has been done in other countries.”

Avoiding immigration phobia

Dr Bob Birrell, president of the Australian Population Research Institute, says survey data collected by the institute and other pollsters shows about half the Australian electorate want a reduction in immigration.

Birrell co-authored a report titled A Big Australia: Why it may all be over, released in October 2020 following a survey of more than 2200 people.

“A majority of all voters think Australia does not need more people and believe that high immigration is responsible for the deterioration of the quality of life in Australia’s big cities, as well as stressing its natural environment,” Birrell says.

“High migration has been a major factor in Australia’s economic growth. But, from the point of view of individual Australians, it’s GDP per capita that counts, and also it’s quality of life that counts.

“That’s a major reason why so many Australians want migration to be reduced.”

Birrell says previous government commitments in the UK and the US to a globalising, high immigration agenda have been successfully challenged by protest movements, represented by Brexit in the UK and Trump’s 2016 presidential victory in the US.

“The story we tell in this report is that Australia, too, is vulnerable to a similar reaction.”

Prior to COVID-19, population growth in Australia had been about 1.5 per cent a year, of which net overseas migration comprised about one percentage point. By contrast, net overseas migration is currently adding 0.3 per cent a year to the population of the US, and 0.4 per cent a year in the UK.

However, Ball says it is important Australia does not make the same mistakes that other countries have made in the past, and guards against some of the negative attitudes about migration that can start to pervade in the current economic climate.

Addressing skills shortages

The federal government has announced that a new whole-of-government Global Business and Talent Attraction Taskforce will be established to attract international businesses and exceptional talent to Australia, to support the post- COVID-19 recovery and boost local jobs.

This builds on the existing Global Talent Initiative and Business Innovation and Investment Program and another initiative announced by the government in July 2020 to attract export-orientated Hong Kong-based businesses to Australia.

Ball says it is vital the Australian Government kick-starts migration levels by addressing skills shortages in the economy, but emphasises the government needs to be completely transparent in its processes.

“We’ve got a temporary program and a permanent program in Australia, which are very focused on skilled migration,” he says.

“But some of the analysis, particularly on the temporary migration around the skills that are in demand, is not particularly transparent.

“That information is going to need to be made a lot more transparent, and the process by which governments arrive at a skills shortage list is going to need to be made a lot more transparent, so the community has confidence that we’re approaching our migration program in the right way for the labour market that we have at the moment.”

In a recent report, CEDA urges the federal government to introduce intra-company transfer visas to encourage multinational businesses aiming to invest and expand their operations in Australia.

“We should use this period to improve on our skilled migration system to ensure that, when the borders open up again, Australia is the destination of choice for the best and brightest,” Ball says.

“We should really be wanting to get out there and get the best global talent here in Australia, so that those people are doing great work in our economic recovery.”

Ball says this talent includes entrepreneurs and people with highly specialised skills that are needed in areas such as manufacturing and technology.

“Those people will actually be job multipliers in a recovery, so we need to make sure we’re getting those sorts of people into the country as well.

“The key here is about our rigour and transparency about our skills shortage analysis and making that public, and having a debate about where the skills shortages are.

“That will ensure that we maximise the economic benefits that we get from migration in a much more difficult labour market, but it will also give the community more confidence that the system is swinging in the right direction at a difficult economic time for the country.”

Germany's migration story

Germany's recently launched Skilled Immigration Act seeks to streamline processes and address skills shortages in growth areas.

Germany, already one of the most popular destinations for migrants because of its strong economy, earlier this year enacted legislation to make it easier for skilled foreign workers from outside of the European Union (EU) to apply for work permits.

Its new Skilled Immigration Act came into effect on 1 March 2020, to streamline the migration processes for workers with vocational, non-academic training from non-EU countries to migrate to Germany for work purposes.

One of the primary aims of the German Government has been to address skills shortages in growth areas such as aged care, information technology and engineering.

The Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce has estimated Germany will find it hard to fill more than 1.5 million skilled jobs over the long term.

An important aspect of the new act is that it effectively gives German companies the green light to hire skilled professionals from any country. That means they no longer have to prioritise hiring either German nationals or workers from within the EU nations.

Furthermore, foreigners without a firm job placement in Germany, but with relevant professional skills in high-demand employment sectors, can now apply for a short-term job seeker’s visa while they look for work.

There are, however, some key stipulations in Germany’s legislation.

Applicants need to prove they have proficiency in the German language and must have either German or equivalent recognised qualifications.

Even still, a major ongoing challenge for Australia in meeting its own employment needs will be competing for skilled professionals with other countries such as Germany.