Loading component...

At a glance

It’s 5.30pm at Sydney Airport and I sit, laptop open, intent on doing some internet research before my flight home.

A few moments later, a thirty-something woman – let’s call her Sue – sits down opposite me. She, too, has a laptop. She plonks it on the bench and sighs: “It never ends, does it?” Her mobile rings and she answers.

“I’ve just got back from training and there are 300 emails in my inbox. And no, we can’t give that extra work to her; it’ll kill her.”

I own up to eavesdropping and mention I’m writing an article on being overwhelmed with work. Another woman nearby looks up from her computer, interested, alert. Soon an intimate focus group is taking place among strangers, catalysed by that one word. Overwhelmed.

You can hear it in the harried tones of fellow workers and see it in the bleary eyes of commuters. The impromptu airport focus group certainly felt it. But does the evidence actually back up claims that we are under more pressure than ever before?

Are we doing it harder?

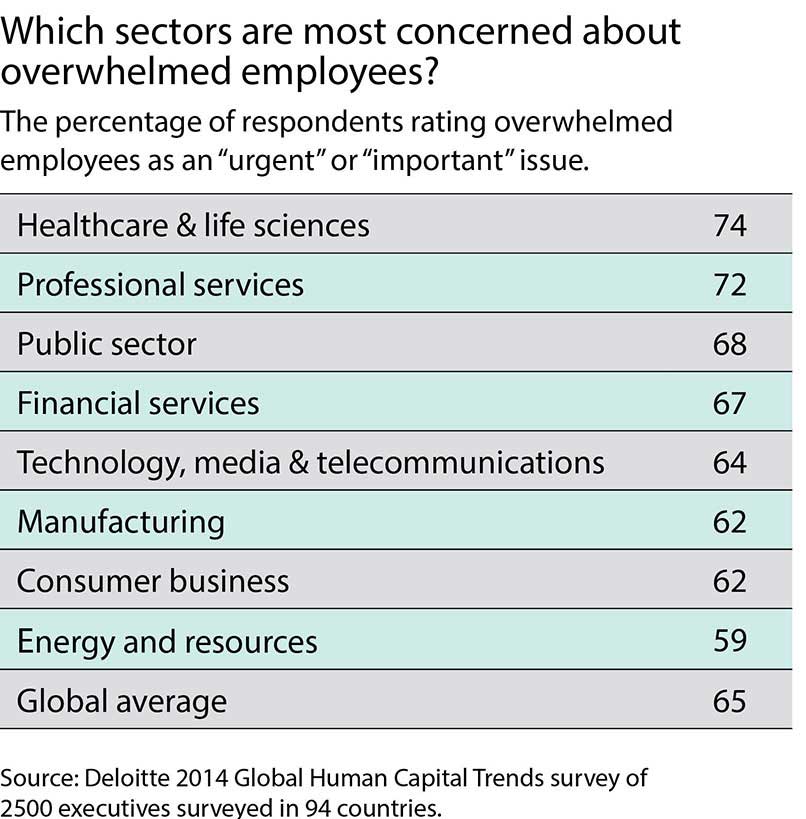

In 2014, a Deloitte survey – Global Human Capital Trends – suggested the answer might be “yes”. Sixty-five per cent of the 2500 executives surveyed in 94 countries rated “the overwhelmed employee” as an urgent or important trend.

To find out more, I visited Deloitte’s head office in Sydney to speak with David Brown, co-author of their Human Capital Trends reports. Deloitte’s media manager greets me, pleased to see a reporter in person.

“We can’t get any journalists to our briefings anymore. They are all too busy as they just don’t have the staff.”

"More professionals will change jobs if organisations don’t get better at dealing with this issue."

Brown says he is not sure if this phenomenon of overwhelm is something new that’s here to stay or if it’s a short-term disturbance during a time of accelerated disruption as we adjust to the data overload generated by technology.

So, are longer working hours to blame?

Apparently not, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Over the past 30 years, average working hours in Australia have decreased. Among full-time workers, hours per week increased in the 1990s to 41 hours, peaked again in 2000 at 41.3 hours, then fell to 39.7 hours per week in 2009, the most recent year for which we have data.

Changes in the proportion of people working more than 50 hours a week follow a similar pattern, increasing from 13 per cent in 1978 to 19 per cent in 1999, before falling to 15 per cent in 2010 after the 2009 economic downturn. Similar trends have been observed in the UK.

Matt Grudnoff, senior economist with The Australia Institute (TAI), is concerned that with the advent of mobile technology, hours spent working at night and on weekends are slipping through the cracks. TAI argues that millions of workers now have their free time “polluted” by work demands, thanks to their devices.

Former Morgan Stanley chief economist Stephen Roach holds the same view. He has criticised “the undercounting of work time associated with the widespread use of portable information appliances”.

Yet it is not easy to see in the published figures.

Are working hours more intense?

When I contact experts in this field, five say they cannot provide comment – they all simply have too much on their plate.

Work intensity is hard to measure, but researchers often look at how often workers report working at high speeds, to tight deadlines and/or managing high workloads.

There is no doubt it shows up in employee surveys as a pain point in many countries, along with stress and work-life interference, especially where there is a culture of long hours, such as in China, Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan.

Exactly how much work intensity has changed over time is hard to say. It is not tracked in the same systematic way as working hours.

Cardiff University’s Skills and Employment Survey, which involves a representative sample of British workers, has data going back 20 years. In 1992, 32 per cent of employees strongly agreed that “my job requires that I work very hard”; by 2012, this number rose to 45 per cent.

Similarly, the 2012 European Working Conditions Survey reports that work intensity has increased in most European countries over the past two decades, although the increase has slowed since 2005.

Yet the Australian Work and Life Index (AWALI) survey found little change in reports of work overload or work-life interference between 2007 and 2012, with one exception – full-time working women’s dissatisfaction with their work-life balance had risen, as had their sense of time pressure.

Back at the airport, Sue tells us she has seen staff become physically ill over the strain. She’ll say only that her employer is in telecommunications.

“Because we are already so thin on staff, when one burns out we feel the impact immediately,” she explains.

“I can tolerate a very high load, but a few weeks ago I came in and only lasted one hour. I put my head on the desk and couldn’t function for the rest of the day.”

Who is under the most pressure?

Managers, women, parents and those who work in big organisations or work 48 hours or more in full-time positions are the most likely to complain about high work intensity or work-life interference.

Occupations in healthcare, education and professional services repeatedly top the list of those most under pressure. In the past decade, recession, job insecurity, increased reporting requirements and globalisation have turned up the heat in these fields.

Professor Paula Brough, from the School of Applied Psychology at Griffith University, points the finger at mobile technology. Her research documents techno-stress as a prime cause of increasing work intensity.

“Technology is offered as a way to improve productivity, but it really is a two-edged sword,” she says.

"Hours spent working at night and on weekends are slipping through the cracks."

There are proven neurological reasons why the brain starts to malfunction in the face of the constant interruptions and information overload that are inherent in technology use. Dr Jemma Harris, PhD in cognitive psychology and lecturer at the Australian College of Applied Psychology, explains how repeatedly switching our attention between tasks depletes the resources of the prefrontal cortex of the brain, which we need for planning, prioritising and higher order decision-making.

Heavy task-switching can leave us physically exhausted, less able to control our emotions, mentally foggy and therefore about 20 to 40 per cent slower at completing tasks.

The prefrontal cortex also has a novelty bias. Every time we turn our attention to some new information, the brain rewards us by releasing feel-good hormones, creating an addictive loop and increasing our desire for distraction.

Yet there is a limit to how much new information we can process. Too much information triggers anxiety and renders us less able to prioritise and focus on what’s most important.

To the rescue

Brown is optimistic that technology will be part of the solution to the “overwhelm” problem. He predicts that artificial intelligence will help us make better sense of all the data being generated and so take some of the intensity out of the equation.

“As well, more professionals will vote with their feet and change jobs or go freelance if organisations don’t get better at dealing with this issue,” he says.

“I hope I’m right. If I’m wrong, the implications for society are massive. Less-skilled workers don’t have the same choices, so they will be hardest hit, and we will continue to see the gap between the haves and the have-nots widen even more.”

Deloitte plans to revisit the “overwhelm” issue in future surveys … when it has time.

Overwhelm: a global issue

- Australia: 30 to 40 per cent of Australian workers report working intensively.

Australian Work and Life Index Survey, 2012 - UK: 41 per cent of employees say they are under excessive pressure at work at least once or twice a week.

CIPD Employee Outlook Survey, 2013 - US: 41 per cent of people report being stressed out at work.

American Psychological Association Workplace Survey, 2012 - Singapore: 55 per cent of senior managers say they are under more stress than in the past five years.

Regus Workplace Survey, 2015 - Hong Kong: 66 per cent feel highly stressed by their jobs.

Occupational Safety and Health Council Hong Kong, 2015