Loading component...

At a glance

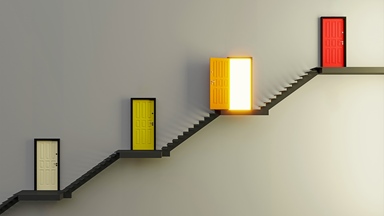

- Strong decision-making is a learnable skill that should be developed early in a career, not just when stepping into leadership roles.

- Effective decisions combine data-driven intuition, adaptive thinking and diverse perspectives, rather than relying solely on technical analysis or AI tools.

- Consistency, stakeholder engagement and post-decision reflection are essential for building trust and improving future decision-making outcomes.

For accounting and finance professionals, decision-making is not an occasional task, it is part of the job.

However, as people step into leadership roles, the stakes of each decision rise. The job is no longer just about reconciling numbers or spotting trends, but about managing risk, guiding investments and influencing outcomes that ripple across the business.

The pressure in today’s workplace is only intensifying. A 2024 Accenture study finds that over 80 per cent of CFOs say the pace for decision-making has become faster in the preceding year.

Despite its central role, decision-making is rarely treated as a core professional skill.

“One of the biggest traps is waiting until you’re in a senior role to build decision-making capability,” says Dani Fraillon, head of partner development at Deloitte Australia. “But the habits and frameworks you form early on are what carry you when the pressure rises.”

Paul Gordon, author and CEO of boutique consultancy Catalyze APAC, agrees. “As people move into more senior positions, there’s an unspoken expectation that they should already know how to make the right calls.

“But decision-making is a discipline — it is something you can learn, develop and support with the right frameworks and tools.”

Decision-making online course

Use adaptive thinking

Accounting professionals often rely on tools, numbers and data to guide their decisions. But as Fraillon points out, “people now have answers at their fingertips on their devices, which means they often haven’t taken the time to think deeply”.

“There’s real value in the kind of intuition that comes from years of working with data,” she says. “It is that gut feeling when something doesn’t seem right, even if everything appears fine.”

Alongside intuition, Fraillon emphasises the importance of adaptive thinking, which is the ability to approach problems from multiple perspectives.

For example, when evaluating a new technology, the technical specs might look perfect on paper, but she encourages asking “What are the elements of that technology that may not work for this organisation based on our culture?”

Embrace perspective

Great decision-making starts with listening to different perspectives. Fraillon says that it is beneficial to harness others’ wisdom early to make sure all sides of a decision are explored.

“Having the right people in the room to disagree means you will not just go to your default, which could be looking at the upside rather than the downside.”

A recent McKinsey study found that high-quality team debates led to decisions that were 2.3 times more likely to be successful.

At Deloitte, Fraillon uses a Business Chemistry framework to make sure people from different backgrounds and personalities are included in decision-making.

“When you have robust conversations with diverse perspectives, you end up with a far stronger decision than if you had a room full of people who all think the same.”

Be reliable

Catherine Simons CPA, managing director of professional services firm WSC Group, says that consistent decision-making is a defining quality for finance professionals aiming to advance their careers.

“People don’t judge you by the best decision you’ve ever made,” she says. “They judge you on your baseline and what they can reliably expect from you day in and day out.

“If you can demonstrate that your decision-making is consistent and fair across a range of situations, people learn to trust that,” she says.

When it comes to junior staff members, Simons adds that a solutions-oriented mindset is often what sets one individual apart from another.

“Typically, what we suggest is starting with smaller decisions on everyday problems,” says Simons. “Supervisors notice when someone consistently makes good decisions — it builds trust and strengthens their case for promotion.”

Avoid people-pleasing

New or inexperienced leaders often feel pressure to keep everyone happy, says Gordon.

“It is really easy to confuse doing what individuals want with doing what is best for the organisation.”

To avoid people-pleasing, he suggests having early conversations with key stakeholders about how the decision will be made. “If someone from the outside says, ‘Look, Paul, you look a bit uncomfortable with this decision’, you’ll probably take yourself out of the decision-making process,” he explains.

“Instead of asking what people think, ask them what factors about this decision impact them,” he says. That way, you focus less on approval and more on getting useful input.

Use AI, don't rely on it

Artificial intelligence (AI) can be a helpful tool in decision-making, but it is not a replacement for human judgement.

“A lot of younger professionals go straight to AI tools like ChatGPT for tactical answers,” explains Fraillon. But relying too heavily on AI can mean missing out on developing the “deeper thinking skills needed for strategic, big-picture decisions”.

"Typically, what we suggest is starting with smaller decisions on everyday problems. Supervisors notice when someone consistently makes good decisions — it builds trust and strengthens their case for promotion."

Agentic AI can now make data-backed organisational decisions and set goals. While that might sound efficient, Gordon warns against handing over our thinking to AI.

“I encourage people to use AI to help with the decision process, but not to take the decision-making away.”

The real danger, he says, is losing agency. “As leaders, we want to take accountability for the decisions that we make.” It may be faster to use technology, but the responsibility should stay with humans.

Decision-making tips to improve your work performance

Utilise four core principles

When a high-stakes decision needs to be made, Gordon recommends relying on four core principles. The first is process.

“Make sure you have a decision process before you make a decision,” he says. Even a simple, agreed way of thinking through the issue can help bring order to chaos.

Second, apply academic rigour. That does not mean needing a PhD, but instead having well-reasoned thinking behind the choice.

“If it is a decision that could impact billions of dollars, you need to be confident that if it is ever tested or audited, you can say, ‘Yes, the thinking behind this was thorough’.”

Third, engage stakeholders. Even under pressure, don’t decide alone.

“Think about who the stakeholders are and find a way to understand how the decision impacts them — maybe even include them in the decision process,” Gordon advises.

Finally, look at tangible and intangible values. Not every outcome shows up in a spreadsheet.

“Every decision has trade-offs in both intangible and tangible outcomes,” he says, giving the examples of time, culture and energy.

Reflect on past decisions

Great decision-makers do not just move on once a choice is made — they go back and examine it.

“Good decision-makers go back and interrogate the decision,” says Fraillon. “Whether it was a good decision and everything went really well, or it was a bad decision and things went pear shaped.”

The goal, she says, is to understand how the decision was made. The questions to ask include “Did we use the process? Did we connect with the right people? Did we influence the right people? Did we have the right information at the time?”

Going back and interrogating the steps of decision-making is as important to the learning as getting the decision right, Fraillon says. It is how leaders and aspiring leaders learn, grow and avoid making the same mistake twice.