Loading component...

At a glance

- For many years, the franchising sector in Australia has been riddled with conflicts and negative publicity.

- The balance of power often favours franchisors due to their size and ability to organise themselves and lobby for change.

- Despite 17 inquiries into franchising in the past 30 years, there has been little change. However, the latest inquiry is expected to improve accountability and protection for whistleblowers.

In some industries, franchisors have been in bitter conflict with their franchisees. The pressure has ruined the lives of many small business owners and led to the exploitation of employees, and even allegations of wage theft.

To these three stakeholding groups, add commercial landlords who rent premises to franchisees and, in some cases – where franchisors have taken their companies public – also add shareholders looking for capital gain, along with regular dividend payments.

These varied interests often compete, and the balance of power has historically been skewed in favour of franchisors, to the detriment of those further along the chain and closer to the customer.

Because they are larger entities at the top of the structure, franchisors are often better at organising themselves and lobbying than franchisees, who may be small family business units isolated from each other and too busy working to organise themselves.

At 9 per cent of GDP, franchising as a business model is perhaps too big to fail, but it stands on the cusp of significant reform.

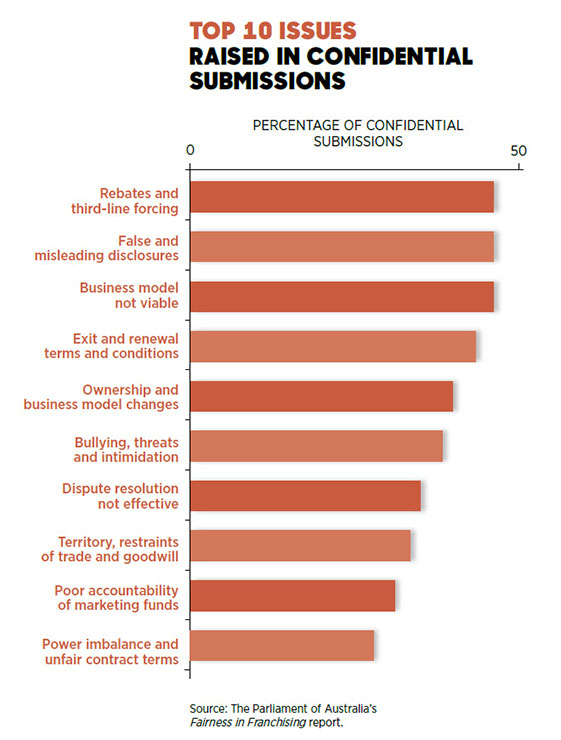

Galvanised by a flood of complaints and negative publicity, the sector attracted the attention of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, which released its Fairness in Franchising report in March this year.

The report’s bipartisan view was damning. The regulatory environment, it said, had “manifestly failed to deter systemic poor conduct and exploitative behaviour and has entrenched the power imbalance”.

“There are deeply rooted cultural problems that will not be resolved by a franchisor replacing a few senior executives,” the report said, as it went on to document a litany of problems, from unfair contract terms and poor transparency and accountability, to a lack of protection for whistleblowers.

Among the report’s recommendations was a toughening of the Franchising Code of Conduct to include civil pecuniary penalties, proposals to give greater enforcement powers to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), and the creation of an inter-agency Franchising Taskforce to implement the changes.

The report is by no means the first to look at franchising. Senator John Williams, who was instrumental in calling for the latest inquiry, noted that in the past three decades, there have been 17 inquiries into franchising, with little result.

Is reform in the franchising sector possible?

This time, however, there is some optimism that reform is possible.

Professor Allan Fels AO, who was the inaugural head of the ACCC in 1995 and was in that role at the birth of the Franchising Code of Conduct in 1998, believes that this time, effective regulation may be on its way.

“I was present at the birth of the Franchising Code, and it was clear from the start that the spirit of that piece of work was not that strong,” he says.

“It was clear that it was likely to be watered down in practice and it didn’t have enough teeth, but now the review proposes giving it some teeth.”

"Too often, franchise arrangements are configured around a hugely profitable head office and franchisees who are barely able to keep their heads above water.”

Where the original code was “towards the tokenistic end of regulation”, Fels describes the new recommendations as “some big steps forward”.

“The report has called out the system very well, and it has basically taken the side of the franchisees, which it should because the system has been dominated by franchisor interests,” Fels says.

“If we can get all the recommendations through the system it would be great, and whether it should go further is a question for another time, but it has certainly gone further than the previous reports.”

The parliamentary report was similar to the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry, in that it brought out a flood of well-reported horror stories, many of them from the fast food and convenience store sectors.

Squeezed by franchise agreements that stripped profits, mandated exorbitant supply agreements and overcharged for ineffective marketing campaigns, some franchisees were so close to ruin that they in turn preyed on those next in line, their employees.

Highly motivated owner-operators

While the media feasted on the negatives, there were many franchisors who made submissions to the inquiry and who never made it into the headlines.

Bookseller Dymocks was one of these. The 140-year-old company began franchising its business in 1986, and 52 of its 56 stores around Australia operate as franchises.

Managing director Steve Cox says he believes the franchise model has helped Dymocks survive in an under-pressure industry, which has seen the high-profile exits of Australian rival booksellers Angus & Robertson and US firm Borders in the last decade.

The combination of a brand such as Dymocks with its buying power, high consumer recognition and highly motivated local owner-operators has been key to the group’s survival and growth, Cox says.

“The locally owned and operated ownership model, with the support of a large and well-known brand, has proved to be a very successful model in our industry and has stood the test of time,” he says.

“Individuals own their own stores and treat them as their own businesses – which they are – but are supported by the Dymocks network, which allows them to focus on their customers and engage with their local readers and curate their stores.”

Dymocks, says Cox, provides training and support, access to processes and proprietary systems built up over decades, salary benchmarking and marketing under the umbrella of a brand that has been a household name for more than a century.

Then there is Dymocks’ centralised buying power, which delivers books to resellers at a lower cost than if they were running their own independent bookshop.

“An individual starting a bookstore from scratch really doesn’t have that depth of experience, but when they join our business they are benefitting from all our experience and that of our other franchisees,” Cox says.

“If you look at everything it takes to be a good retail store and a good bookstore, all of these are solved for a new entrant who is a Dymocks franchisee.

“We are focused on making sure that people who join Dymocks as a franchisee make the most of their investment and maximise their profitability from the beginning, because their success is our success.”

Other submissions to the inquiry came from law firms representing employees who are both at the bottom rung of the franchise industry as well as being at the coalface.

Patrick Turner, an associate with Maurice Blackburn, says the firm’s submission was focused on the issue of wages theft and, in addition to recommendations on penalties, included the idea of a “funder of last resort”, so that employees would be ensured payment in the event of a franchisee going into liquidation.

Maurice Blackburn is also concerned at the incidence of “phoenixing” by franchisees, where they create new companies to escape the debts and obligations of former companies.

“Too often, franchise arrangements are configured around a hugely profitable head office and franchisees who are barely able to keep their heads above water,” Turner says.

“Any business model that ultimately leads to employees not even being paid legal minimum wages is not one we think is fit for purpose.”

Turner agrees that the committee report includes some positive recommendations, but believes that more needs to be done “to ensure that franchise head offices take responsibility and don’t ultimately leave their workers footing the bill”.

In the regulatory sphere, Turner says that too often franchising issues have “fallen between the cracks” between different agencies, and welcomes the idea of a taskforce working with the ACCC as a way of driving oversight.

“Yet we don’t feel the report goes far enough,” he says.

“We wanted a positive obligation to be placed on franchisors to ensure that their franchisees are upholding the legislative requirements of workplace law, and we are disappointed not to see that.

“While there have been some moves with the passage of the Protecting Vulnerable Workers Act, there are still too many loopholes in the law and it’s too easy to escape liability.

We think more needs to be done to ensure that franchisors are stepping up to the plate.”

Underpayments in franchising

Fels’s work crossed over with some of the themes of the franchising enquiry in his role as head of the Migrant Workers’ Taskforce earlier this year, and he agrees that underpayment in franchising has become “systemic” because of the pressure of “tough profit sharing arrangements” on franchisees.

The Migrant Workers’ Taskforce report recommended moves to criminalise wages theft, but while this has been welcomed by members of the parliamentary inquiry, it has a long way to go before becoming law.

Ultimately, Fels remains positive about the franchise model, which he believes will “long survive” if it is reformed with adequate “checks and balances” for franchisees and employees. While the report is a good first step, implementing it will be a longer road.

“Reforms like this are often undermined in the implementation process,” Fels says.

“I forecast heavy lobbying and attempts to water down the recommendations by franchisor interests.

“Sometimes an industry accepts a voluntary code without sanctions because it’s a way of deferring real government action, and while that may have been true with the original Franchising Code, I am optimistic that we are finally moving in the right direction.”