Loading component...

At a glance

As Australian university student Philip Brown packed his meagre belongings and prepared to leave everything behind to study at the University of Chicago, his vision of the next few years was not a positive one.

It was 1963, but his dark mood had nothing to do with the momentous events going on around him – the year the Viet Cong won their first major battle, marking a turning point in an already unpopular war, The Beatles released their debut album titled Please Please Me, John F Kennedy was assassinated and Martin Luther King Jr delivered his “I had a dream” speech. Instead, his malaise was brought on by matters of the heart.

Having accepted a Fulbright Travel Scholarship to earn a PhD, after graduating with honours in accounting at the University of New South Wales, the 23-year old was leaving behind Edith who, he says 55 years later, was his “very, very, very close friend”.

“We parted on the understanding that if I found somebody who appealed to me more or she found somebody who appealed to her more, then that would be OK,” Brown, now emeritus professor and senior honorary research fellow at the University of Western Australia and a fellow of CPA Australia, recalls. Even so, of course, the thought terrified him.

“What could I do? I was a poor student. I didn't even have the money to make long-distance phone calls and email didn't exist. It was very difficult to leave her behind."

Fortunately, Brown would find a worthy distraction from his lost love soon after arriving in Chicago. However, it wouldn't come in a female form – that wound was too fresh. Instead it was an academic challenge, one that would define his entire career.

An environment of innovation

In the early to mid 1960s, the finance world had a very low opinion of accounting, particularly in terms of financial statement information. The generally accepted wisdom was that such accounting was of no value in the assessment of a business’s worth, and was therefore completely unrelated to such investment matters as stock prices. It’s an attitude that seems absurd today.

The respect in which accounting is currently held is partly due to the work done by two young Australians at the University of Chicago. One was Philip Brown. The other was Ray Ball, who arrived at the university’s hallowed halls a few years after Brown.

“When I arrived the place just crackled with ideas,” Ball, who was four-and-a-half years younger than Brown, says.

“You would walk into the faculty lounge and say something and someone would immediately get up and start writing on the blackboards, trying to dissect the idea, pull it apart and play with it.

“For 100 years this university had celebrated the innovation of new ideas across a range of areas, so the business school at the University of Chicago basically became the most innovative business school in the world. We’ve now had eight Nobel Prize winners on our faculty, so it’s part of the culture.”

“Ball and Brown 1968”: an academic icon

The idea that Ball and Brown challenged was the one around the value of accounting. The lowly opinion of the profession came from the fact that, at the time, there were so many different methods accountants could choose to produce various financial results. It led to the belief that number crunchers were simply employed to hoodwink investors or creditors.

This was a serious issue at the time. An academic paper written by another Australian accounting heavyweight, R.J. Chambers, concluded that from a single set of organisational transactions, the various accounting methods available meant it was possible to report 30 million different profit figures. Another problem was historical-cost accounting, which did not take inflation into account and therefore, on balance sheets, did not compare like with like.

Ball and Brown believed that accounting would never have played such a central role in business and finance for so many centuries if it truly lacked value and meaning.

They decided to run a study, which, put very simply, would find out whether and how share prices had reacted to information captured in financial statements in the past. The pair did so by crunching big data, and the data really was big. The computer (the only one at the University of Chicago) filled two rooms!

“It took up an enormous space, but the size of its memory was one two-millionth the size of my iPhone’s memory,” smiles Ball, who is now the Sidney Davidson Distinguished Service Professor of Accounting at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

“When one person was running a job on it, nobody else in the university could do any computing. The file of historical stock returns was on magnetic tape that took three minutes for the computer to read from one end to the other.”

The results of their study empirically demonstrated for the very first time that accounting figures were of immense value to investors. Accounting reports, such as annual reports, profit reports and profit warnings, correlated directly with shifts in stock prices.

"We've now had eight Nobel Prize winners on our faculty, so it's part of the culture."

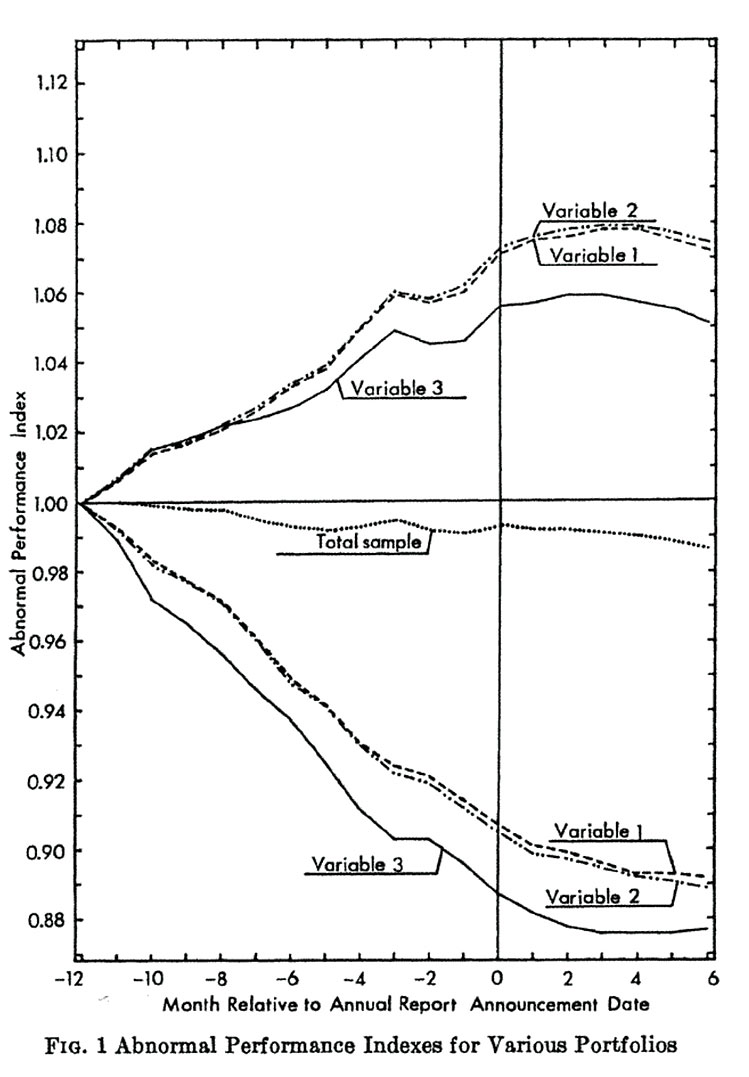

Also, the now famous “Figure 1” graph in their published paper – “Ball and Brown (1968): An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers” – clearly illustrated the fact that the market anticipated profit reports, building value into a stock (or taking it away) in the lead-up to a report, as well as responding with a rise or fall in value after a report’s release.

The article was originally rejected by The Accounting Review, partly because it was all but impossible to find a referee with the knowledge to handle the submission, but also because editors felt it had “little to do with accounting”.

However, in 1968, when Nicholas Dopuch (also remembered as a transformational figure in accounting research) was appointed as editor of The Journal of Accounting Research, the study finally earned its place in history.

The result

In the pre-internet era, news didn’t spread quickly. Ball and Brown returned to Australia and got on with their lives. Academics mostly reacted to their paper with indifference. The typical financial academic, Brown says, went on believing financial statement information meant nothing. Still, in the absence of the two young Australians, their research study took on a life of its own.

As more academics cited “Ball and Brown (1968)” in their own work, people began to take notice. Eventually, those in the academic and financial realms recognised the work as a true classic.

“Overall, ‘Ball and Brown (1968)’ expressed a view of information in markets that was new to the accounting literature, and contributed to a sea change in attitudes toward financial markets, disclosure, and financial reporting,” the pair wrote in a 2014 paper called “Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective”, published in The Accounting Review.

“Viewed more generally, the research demonstrated that accounting is a viable area for market-based and information-economics reasoning, at a time when these areas were just being developed. It helped elevate the status of accounting research among colleagues in adjacent areas and in universities generally. We are fortunate and proud to have authored it.”

Ball was just 26 when the University of Queensland appointed him as a full professor in August 1971. He was told at the time that he was the second-youngest professorial appointment in any area in any Australian university. The youngest was Enoch Powell, who became a full professor of ancient Greek at the age 25 at the University of Sydney and who later became Britain’s Minister of Health.

Brown and Brown (1966)

Having spent more than three years in Chicago, faithfully exchanging letters with Edith twice a week, every week, Brown returned to Sydney and into the arms of his one true love. They were married in September 1966, the same year Harold Holt became prime minister of Australia, England beat West Germany to win its only FIFA World Cup, and The Beatles recorded Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Now, in the 50th anniversary year of the publication of “Ball and Brown (1968)”, Edith and Philip celebrate an equally important milestone – 52 years of marriage.

“I think Edith has our letters in a box somewhere,” Brown says. “At the University of Chicago, I did this one thing that everyone will always remember, which is quite wonderful, but those letters shaped my life just as powerfully.”

Q&A: Researching the researchers

Dr Bryan Howieson FCPA from the University of Adelaide had Professor Philip Brown as an accounting lecturer at the University of Western Australia. Howieson was recently funded through the CPA Australia Global Research Perspectives Program to produce a reflective, historical piece on “Ball and Brown (1968)”.

What drove the research study?

Ball and Brown couldn't understand that if accounting numbers really were meaningless, why the profession had persisted for so many centuries. They wanted evidence about whether accounting numbers had relevance.

Why hadn't anybody else thought of this?

Actually, they had! There's a paper from 1961 that tried to do something very similar. It remained in obscurity because the researcher didn't have the computing power, the dataset or the advances in finance theory that were available to Ball and Brown.

People distrusted accounting because of the many ways to develop financial results. Has accounting improved since then?

I think the problem persists, but for a different reason. Now we have a well-established set of standard that restrict the numbers of choices, so it's nothing like what it was in the 1960s, but there are a lot of measurements we make that are estimates of the future and there are still choices within standards.

I believe there's a theory that says great research projects such as "Ball and Brown (1968)" had something to do with space exploration?

Nicholas Dopuch, the journal editor who accepted the paper, wrote later that he thought one of the primary catalysts for all of the brilliant research work of the time was the launch of Sputnik 1.

His argument is that Americans became so embarrassed at falling behind the Russians in the space race that they started up a major movement to improve the quality of education across the nation. This brought a greater focus to maths and statistics. I like to joke that Ray and Philip were influenced by communism!

The legacy lives on

CPA Australia has funded new research: “Decision usefulness in financial reports” by academics from the University of Melbourne and Monash University. This work adds to the ongoing global debate into the value and relevance of financial reports that originated with Ball and Brown’s research in the 1960s.

Go figure!

“Figure 1 from ‘Ball and Brown (1968)’ has become one of the most recognised graphs in academic research,” Brown says.

“I originally drew it myself. Then one of my former MBA students, who happened to be a draughtsman, saw it, raised his eyebrows and said, ‘I think I can do better than that!’ And he did.”