Loading component...

At a glance

It extended over two to three weeks, for several hours a day, and when the process finally came to an end, he felt battered and exhausted. That’s how Chris Brooks, now chief executive of Federation Square in Melbourne, remembers a gruelling recruitment process for a senior executive position much earlier in his career.

“The board considered the previous man to be a psychopath … and they wanted to make sure I wasn’t one,” he says. “They put me through the whole range, including timed numerical, verbal and spatial tests. The most terrifying part was a face-to-face with a psychologist who adopted an aggressive approach to see how I would react.”

Assessed as being of sound character, Brooks was offered the job. “It was quite unsettling at the time, but in hindsight I can understand why they did it,” he says.

The cost of poor recruitment is high. Estimates suggest that to replace someone in a skilled position, the bill can total 150 to 300 per cent of the employee’s annual salary. For executive roles, that can often be more than A$1 million.

The psychometric fix

Psychometric testing has a long history, reputedly dating back thousands of years to China where tests were used to select better educated workers for the public service.

In the Western world, work-related psychometrics really came to the fore in World War I, when the US Army used its “Alpha” test, including measures of verbal and numerical ability, as well as ability to follow directions, to cull the “feeble-minded” and detect leadership potential.Psychometric tests measure a person’s abilities, attitudes, personality and motivation.

They are just one set of tools that employers turn to for added rigour in their pursuit of the perfect match. And according to Hudson’s The Hiring Report: The State of Hiring in Australia 2015, their use is on the rise. Forty per cent of the 3228 Australian professionals they surveyed said they were seeing more psychometric testing compared with two years ago.

"Some of our greatest leaders, such as Churchill or Apple's late Steve Jobs, have been unusual characters who were certainly not agreeable."

Hudson’s own talent management business for the Asia-Pacific has seen a 28 per cent growth in the use of psychometric tests in the past year, says its organisational psychologist, Dr Crissa Sumner. “The greatest demand has typically been for recruitment at senior executive levels, or to cull large numbers of graduate applications, but we are now seeing organisations realising they can use psychometric assessments across their workforce to generate data about the organisation’s capability.”

This is the sort of ‘talent analytics’ that the LinkedIn Talent Solutions guide calls a must-have recruitment strategy for 2015.

“We are also seeing a shift away from hiring for know-how, which you can train later, toward hiring for can-do (capability), want-to (motivation) and cultural fit, which these tests can also assess,” says Sumner.

The appeal of assessments that package the complexities of human nature into neat categories is self-evident. And given our age-old fascination with ourselves, it’s no wonder that these tests, which offer a selfie of our psyche, grab our attention.

Testing the tests

But are they “the ultimate guide to getting ahead”, as described in Hudson’s report? Psychometric tests have certainly come a long way from the more clinically oriented assessments found in workplaces 40 or so years ago. It was around this time that one of the biggest international players in psychometrics entered the field.

“When I first looked at these tests in the late 1970s, I couldn’t believe the questions that were being asked,” says psychologist Professor Peter Saville, the founder of Saville Consulting, which now operates in more than 50 countries around the world. “For example, you could have been asked, ‘Do you often wonder if there is something wrong with your sex organs?’”

Saville seized the opportunity to make these tests relevant and acceptable to the workplace, and “they sold like hotcakes” he says with some satisfaction. His belief in their accuracy shows on the home front, too: he uses ability tests to screen nannies for his five-year-old twins.

Organisational psychologist Scott Ruhfus, managing director of Saville Consulting Asia Pacific, believes that the most significant recent change in the field has been the marked increase in the number of test providers, in what is essentially a self-regulated market.

In the UK, the British Psychological Society accredits psychometric tests and requires that testers are trained in their use and interpretation, but Ruhfus warns that there is no strict accreditation in other jurisdictions.

So how do these tests fare in the hands of consultants and HR practitioners with varying degrees of expertise?

Unsurprisingly, the opinions from HR practitioners vary widely. LinkedIn forums give a flavour of the debate: comments range from “unimpressed” and “at best, an indicator, at worst they pigeonhole people”, to “tremendously useful when used in a scientific manner”.

Research indicates that when used well, relevant aptitude tests outperform resumes, educational qualifications and references by a factor of three to four.

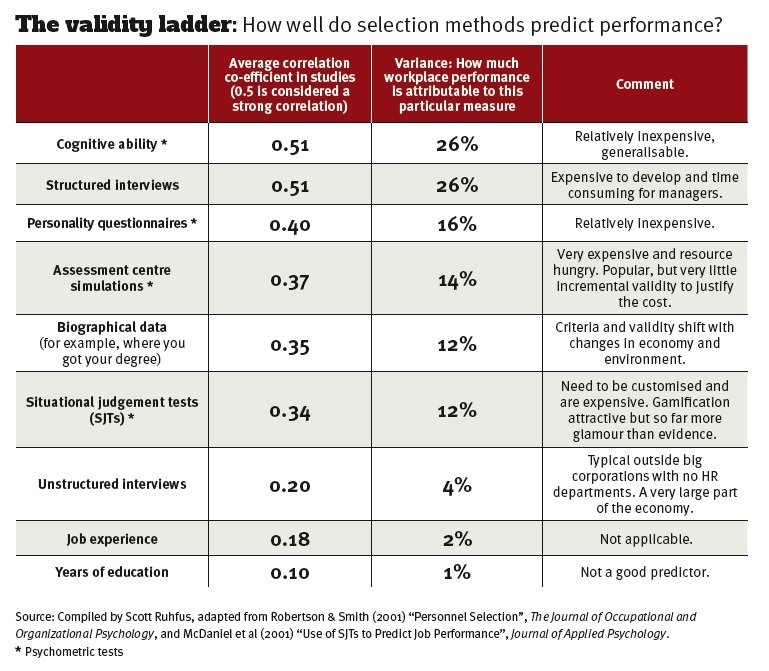

“An overwhelming body of research shows that mental ability tests and structured interviews based on a good job analysis are the most valid methods for predicting how somebody is likely to perform in the workplace,” says Ruhfus.

“They each have a correlation of around 0.5. Compare that to an unstructured interview with a correlation of 0.2, or years of education, 0.1.” (A correlation of 0.0 would represent no relationship between a test and workplace performance, while larger numbers, up to a maximum of one, represent a stronger relationship.)

“When you combine a structured interview with ability testing, it gets up to [a correlation of] 0.63,” Ruhfus explains. “In the social sciences, 0.5 is regarded as a strong relationship.”

What does this mean in practice? How much can psychometric testing improve on the traditional methods of selection, such as interviews and experience? Saville knows the numbers well.

“By using carefully selected spatial, verbal and numerical ability tests for the UK Civil Aviation Authority, we were able to reduce the attrition rate of air traffic controllers from 50 per cent over three years down to 10 to 15 per cent,” he says.

To get these kinds of results, you need to be crystal-clear on what you want to measure, then select a test that’s fit for purpose, advises Melbourne-based clinical psychologist and corporate consultant Simon Kinsella. That means, for example, not using the world’s most popular test, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, for recruitment; it’s not designed for that purpose.

“Ask to see the data that shows it’s a reliable test that will give the same result over time, and that it’s a valid test, truly measuring what it says it does,” Kinsella advises. He uses psychometric tests as a duty-of-care measure to screen out anxiety-prone contestants for reality TV shows such as MasterChef, Australia’s Next Top Model and The Bachelor. Even so, he warns “Use multiple sources of information, not just the test results."

Cindy O’Dea stopped the psychometric testing when she became human resources manager for the Town of Mosman Park local government area in Perth, Western Australia.

“Psychometric tests were being done routinely where the tests were very generic, the results weren’t looked at properly and indicators arising from the tests were sometimes ignored,” she explains. O’Dea now uses them only for staff joining their leadership team, to good effect.

According to Ruhfus, the single biggest problem across sectors is that the job analysis and competency framework used as a basis for selecting appropriate tests is poorly done.

“The worst-case scenario we’ve seen is when companies use these tests to decide who to exit from the organisation,” Ruhfus says.

“That’s not what these tests are designed to do. Actual measures of on-the-job performance should be used for that purpose, not predictors.

“I’ve advised two large, well-known organisations against using tests to decide who to make redundant. One took my advice and the other didn’t. The latter subsequently got very bad press about it. This kind of misuse also gives the tests a bad name.”

Measuring personality

The assessments that seem to attract fiercest debate are the personality tests. And not just because they seem prone to “faking” better scores – something psychologists insist is actually very hard to do with quality tests.

In her 2005 book The Cult of Personality, author Annie Murphy Paul contends that personality tests produce descriptions of people that are nothing like human beings as they actually are: complicated, contradictory and changeable across time and place.

Professor Robert Spillane of the Macquarie Graduate School of Management is also concerned that screening out “difficult” personalities breeds mediocrity and conformity.

“Some of our greatest leaders, such as Churchill or Apple’s late Steve Jobs, have been unusual characters who were certainly not ‘agreeable’,” he points out.

Psychometric tests have been around for 100 years, are here to stay and will continue to evolve. The big challenge for test developers will be to keep up with the rapidly changing nature and requirements of the workforce. Faced with thousands of tests to select from – including gamified testing scenarios, and tools that create psychological profiles from your social media footprint – employers and HR practitioners will need to keep up-skilling to ensure ethical, best practice testing.

Taking the tests

For aspiring candidates who have little choice about whether to do the tests, what’s the best approach? Chris Brooks suggests getting used to performing under pressure.

“With the timed tests, the adrenaline immediately kicks in and you can start to panic.” Psychologist Simon Kinsella’s advice is to relax and aim for the best representation of who you are rather than train up on tests or try to second-guess what the employer might want to see.

“It’s all very well to get yourself across the line but it will end badly for everyone if you can’t actually carry it off.”

The types of psychometric tests

Examples of assessments of maximum performance:

- reading fluency, spelling accuracy, grammatical understanding

- reasoning: verbal, numerical, abstract, logical, spatial, mechanical

- clerical/error-checking ability

- physical: manual dexterity, physical strength, sensory abilities (sight and hearing)

Examples of assessments of typical performance:

- personality questionnaires

- careers inventories

- interest inventories

- 360-degree surveys (where other people rate an individual’s performance)

- motivation questionnaires

- organisational climate/culture surveys

- team roles/participation questionnaires

Situational judgement tests (SJTs), asking individuals to provide a judgement about what they think they would do in certain workplace situations.

Source: Psychometrics @ Work, Peter Saville and Tom Hopton.

How to use psychometric tests for recruitment

- Undertake a thorough job analysis to identify the capabilities and competencies required of the job.

- Select valid and reliable tests that are fit for purpose. Don’t use a test for something it wasn’t designed for.

- Develop skills in giving appropriate feedback, which should never involve a clinical diagnosis. Create the opportunity to explore any apparent inconsistencies in test results.

- Complement test results with other sources of information about the candidate.

Sources: Scott Ruhfus, Peter Saville, Simon Kinsella.